Minimal MQTT with Micropython

I have been meaning to play around with MQTT for some time now, and finally decided to take the plunge one evening last week. I had three cheap home temperature and humidity sensors, and was bothered that they often didn’t agree. Surprisingly, while the analog one had a calibration adjustment in the back, I have no idea how to calibrate the two digital ones. I took this as a sign that it was time to learn MQTT and be able to install my own, accurate sensors. Of course, I began by ordering the cheapest sensors I could find, but I can always upgrade later on.

While we have written quite a bit about MQTT in Hackaday, I had to go all the way back to 2016 to find this introductory four-part series by Elliot Williams. Five years is a long time in the tech world, but I decided to give it a try anyway.

Building a Broker

The first article worked perfectly, although instead of a Raspberry Pi, I used an old desktop that my wife was about to throw away. After wiping out Windows, doubling the RAM, and installing Debian, I had a new lab machine up and running. I installed the mosquitto packages from the standard repositories, and used them without issues to follow along with this article (I briefly tested on an Ubuntu and Mac machine, too). Installation is as easy as:

- Debian and Ubuntu

sudo apt install mosquittosudo apt install mosquitto-clients

- MacOS

brew install mosquitto

Networked Nodes

The trouble began with the second article. Elliot used an ESP-8266 module and NodeMCU. I had been wanting to give NodeMCU a try, so I plunged ahead. While I didn’t have any 8266 modules on-hand, I did have an ESP32 DevKitC module. In the past I brought up these and similar modules running GRBL, Micropython, and bare metal — “How difficult could this be?”, I thought to myself.

Well, in fact it proved to be quite difficult. I proceeded to build NodeMCU custom images online, was able to make the esptool.py talk to and program my board. But try as I might, and I tried for hours, I could not get my board to boot up without errors. The board programmed and hashed correctly, but always gave errors on boot. I read many similar reports from users online, so at least I am not alone in my problem in my frustration.

I reached out to a couple of professional programmers, and the advice I got was to move on. They suggested that NodeMCU is outdated and weren’t surprised I was having difficulties. I am confident that I could have eventually made NodeMCU to work — evidence points to a hardware bootup issue (I/O pin or setting), the online image was being loaded at the incorrect address, or it was just plain wrong. But after so many wasted hours, I wanted to experiment with MQTT, not become a NodeMCU expert.

Having used Micropython before, and seeing there was an MQTT module I could just import, I decided to take this approach. The toolchain setup is a bit involved, but the instructions in the Micropython Github repository were easy enough to follow.

Information about the MQTT server in Micropython can be found here, and I found this two-part tutorial by [boneskull] quite helpful as well:

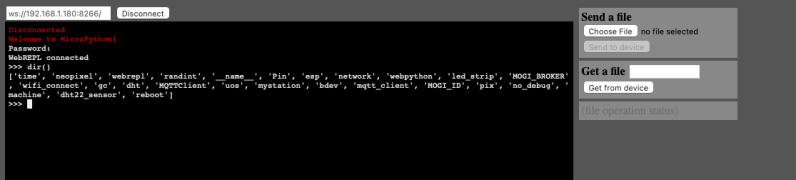

Once everything was all installed, I could pop into a REPL and start programming. I typically use rshell when using Micropython on embedded systems:

pip install rshell

rshell --editor nvim --port /dev/cu.usbserial-1410 --baud 115200

If you prefer to connect wirelessly, there is also the WebREPL method which I tested and seemed to work fine. And of course you can just connect with a terminal emulator but file saving and editing becomes an issue.

I made my demo sensor node along the same lines as the one in the original article. See this Github repository which contains the resulting Micropython flash drive. Copy this to your board, editing the MQTT and WiFi details:

MOGI_ID = 'esp32a-mogi'

MOGI_BROKER = 'underdog.lan'

WIFI_SSID = 'Covid-19-Laboratory'

WIFI_PASSWORD = 'yourpasswordhere'

Enter the REPL using rshell or whatever method you prefer, and start the node by running mystation(). Once it’s tested out, you can make a main.py file so it will auto-start on boot if desired. (Note: MOGI is the Korean word for mosquito.)

Control and Clients

I didn’t go too deep into the third article in the series. I did find a couple of iOS apps which played well with my server out of the box.

Power and Privacy

I think the meat of the final article is still valid. I haven’t put my test sensor node on batteries yet, so I can’t confirm these numbers. That will be a project for another day.

All in all, the basic material in Elliot’s original series is still relevant today. Not surprisingly, the software details have changed a little over the years. Rather than digging myself into a deeper hole with NodeMCU, I switched up and got a similar demo up and running with Micropython. Now that I’m hooked on MQTT, I’ll be delving deeper into battery powered nodes and pretty graphical displays of data before long. My ultimate plan is to hack my home’s automation network.

Post a Comment