BASIC: Cross-Platform Software Hacking Then And Now

Surely BASIC is properly obsolete by now, right? Perhaps not. In addition to inspiring a large part of home computing today, BASIC is still very much alive today, even outside of retro computing.

There was a time, not even that long ago, when the lingua franca of the home computer world was BASIC. This wasn’t necessarily always the exact same BASIC; the commands and syntax differed between whatever BASIC dialect came with any given model of home computer (Commodore, Atari, Texas Instruments, Sinclair or any of the countless others). Fortunately most of these licensed or were derived from the most popular microcomputer implementation of BASIC: Microsoft BASIC.

BASIC has its roots in academics, where it was intended to be an easy to use programming language for every student, even those outside the traditional STEM fields. Taking its cues from popular 1960s languages like FORTRAN and ALGOL, it saw widespread use on time-sharing systems at schools, with even IBM joining the party in 1973 with VS-BASIC. When the 1970s saw the arrival of microcomputers, small and cheap enough to be bought by anyone and used at home, it seemed only natural that they too would run BASIC.

The advantage of having BASIC integrated into these systems was obvious: not only were most people who bought such a home computer already familiar with BASIC, it allows programs to be run without first being compiled. This was good, because compiling a program takes a lot of RAM and storage, neither of which were plentiful in microcomputers. Instead of compiling BASIC source code, BASIC interpreters would interpret and run the code one line at a time, trading execution speed for flexibility and low resource use.

After turning on one’s microcomputer, the BASIC interpreter would usually be loaded straight from an onboard ROM in lieu of a full-blown operating system. In this interpreter shell, one could use the hardware, write and load BASIC programs and save them to tape or disk. Running existing BASIC code as well as compiled programs on one’s computer, or even typing them in from a listing in a magazine all belonged to the options. As BASIC implementations between different home computers were relatively consistent, this provided for a lot of portability.

That was then, and this is now. Are people actually still using the Basic language?

BASIC Joystick Fun

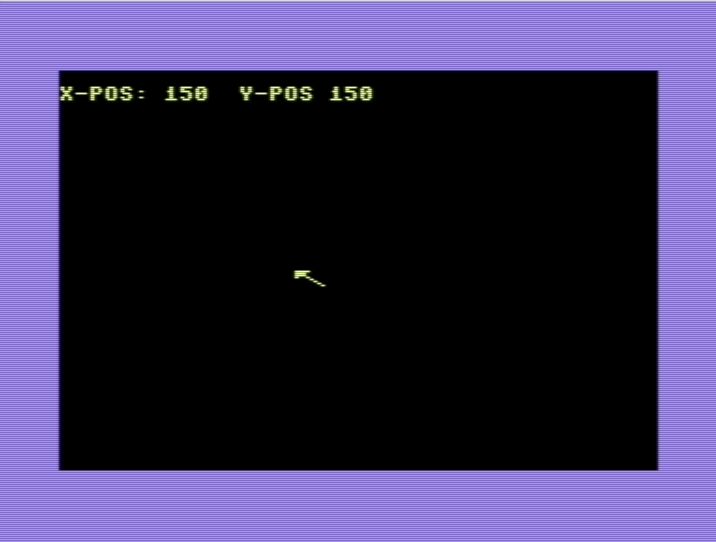

To start off with, let’s see a bit of what BASIC is about. For an extremely simple but fun example of how BASIC can be used, let’s take a look at an application for the Commodore 64 (courtesy of C64-Wiki) that moves an arrow around the screen while printing its screen coordinates using a joystick connected to the second joystick port. The C64 runs Commodore BASIC 2.0, which is based on Microsoft BASIC.

10 S=2: X=150: Y=150: V=53248: GOTO 100 15 J=PEEK(56320): IF J=127 THEN 15 20 IF J=111 THEN POKE 56322,255:END 25 IF J=123 THEN X=X-S 30 IF J=119 THEN X=X+S 35 IF J=125 THEN Y=Y+S 40 IF J=126 THEN Y=Y-S 45 IF J=122 THEN Y=Y-S 50 IF J=118 THEN Y=Y-S 55 IF J=117 THEN Y=Y-S 60 IF J=121 THEN Y=Y-S 65 IF X=>252 THEN X=10 70 IF X=<10 THEN X=252 75 IF Y>254 THEN Y=44 80 IF Y<44 THEN Y=254 85 PRINT CHR$(147);CHR$(158);CHR$(17);"X-POS:";X;" Y-POS";Y 90 POKE V,X:POKE V+1,Y: GOTO 15 100 FOR Z=832 TO 853 : POKE Z,0: NEXT Z 105 FOR Z=832 TO 853 STEP 3: READ J: POKE Z,J: NEXT Z 110 POKE V+21,1: POKE V+39,7: POKE V+33,0: POKE V+29,1 115 POKE 56322,224: POKE 2040,13: GOTO 85 120 DATA 240, 224, 224, 144, 8, 4, 2, 1

Each of the lines above are entered as-is, including the line number. On the next line after the code we enter RUN and hit ‘Return’ (or ‘Enter’, depending on one’s keyboard). Assuming we didn’t mistype anything, the code will now execute to show the following screen:

So what does this code do? As with any BASIC program, it starts at the first line which here is 10. It defines a few variables here, before jumping to line 100 (using GOTO). In a FOR loop, we POKE (i.e. write a hardware register) and repeat this in a few more addresses, which updates the display to its initial configuration. Here the READ command is used to read constants which are defined by DATA.

Many of these memory addresses directly address the video adapter (VIC-II in the C64). When we use PEEK at line 15, it reads the contents of the memory address 56322, which corresponds to the current input values on the second joystick port. After that we can check the state of each input using the bit values and adjust our on-screen arrow accordingly (line 90), along with the coordinates (line 85).

The C64 Wiki page for this program includes a bitwise comparison version. That should run marginally faster, as it has fewer lines of code. For moving an arrow around the screen, the difference would be unlikely to be noticed, however.

Important to note here is that BASIC implementations on different microcomputers would have to POKE and PEEK different memory addresses to get the same effect due to the different system layout of each computer. Some implementations would also provide commands tailored specifically to that microcomputer system, which became more relevant as graphics and audio capabilities grew.

Interpreted Versus Compiled

The interpreted nature of BASIC on most microcomputers was both a benefit and a disadvantage. On one hand, it’s very flexible, and you can simply run your latest program and quickly modify it without having to deal with lengthy compile cycles (on a <10 MHz Z80 or 6502 MPU, no less). On the other hand, because any errors in the code will not become apparent until the program is run by the interpreter, this leads to the same joyful experience as with modern-day JavaScript and Python scripts, where the code will run fine until the interpreter suddenly keels over with an error message (if one is lucky).

With BASIC this usually comes in the form of a ‘Syntax error on line <line>’ error. Running the same code through a compiler would however have found those errors. This feature of interpreted code means that the easy distribution method of code as listings in computer magazines and reference books would only be as good as the quality of the printed code and one’s own typing skills. Fortunately, on the C64 and similar systems, fixing a mistyped line would be as easy as retyping it, hitting ‘Return’ and the interpreter shell would update the line in question.

BASIC Today

All good and well, you may say at this point, but nobody is dragging out that C64 to do some BASIC programming today. Aside from folks who like to play with old computers, of course. Here it should be noted that BASIC didn’t live and die with Commodore and Atari. Over at Microsoft, BASIC spawned Visual Basic, Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and VB .NET. The latter allows writing VB code for the .NET runtime.

Microsoft also released Small Basic in 2008, which it says targets novice programmers, for example students who used a visual programming language like Scratch previously. This is not to be confused with SmallBASIC, which is an open source (GPL) BASIC dialect with accompanying interpreters for modern platforms.

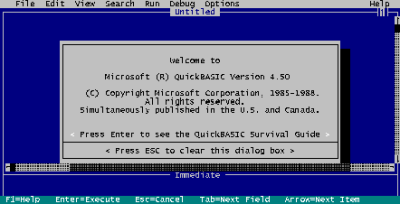

BASIC dialects can also be found in many graphing and programmable calculators from Ti, HP, Casio and others, although many of these dialects are not directly compatible with the original BASIC standard (ISO/IEC 10279:1991). Since the 1980s, BASIC evolved to no longer require line numbers, instead using labels which it can jump to, along with adopting new programming paradigms. This was introduced with QuickBasic in 1985 and is a common sight today.

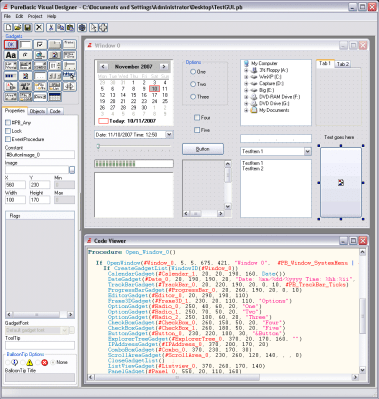

Also on the commercial side of the fence is PureBasic by Fantaisie Software, which provides an IDE and compiler for a number of target platforms. True BASIC is a modern BASIC toolchain and IDE which moves closer to FORTRAN in its syntax, and is developed by the original developers of BASIC (Darthmouth BASIC).

In terms of today’s open source BASIC interpreters and compilers, there is Chipmunk Basic, which dates back to the Apple MacIntosh, Microsoft recently open-sourced its GW-BASIC, and you’ll even find a healthy OSS ecosystem around BASIC. If none of that tickles your fancy, you can implement Tiny BASIC, straight from the BNF grammar as listed in the first issue of Dr. Dobb’s Journal from 1976. A few years ago our own Tom Nardi wrote about his experiences bringing a 1990s QuickBasic project into the modern world with QB64.

Making the case for BASIC

Clearly, BASIC is not dead then. It sees daily use in its commercial forms, the myriad of open source projects and in the vibrant retrocomputing community. Aside from still being a (arguably) good language to teach programming with, it’s also a nice option for embedded applications, especially where many use MicroPython or kin today, as the system requirements are much lower. We reported on an ARM MCU which came with a BASIC interpreter a number of years ago, for example.

There are also projects like UBASIC PLUS on GitHub, targeting STM32F0 MCUs and requiring as little as 8 kB of RAM and 64 kB of Flash. Another project for ARM and PIC32 (as well as DOS and Windows) is MMBasic, which lists its requirements as 94 kB of Flash and at least 16 kB of RAM.

With BASIC having evolved in an era when home computers had less memory and storage than a $5 microcontroller has today, it makes for an excellent, low-resource language for situations which call for the use of interpreted scripts rather than precompiled binaries, without having to shell out for MCUs with more Flash and RAM.

Are any of our readers regular users of BASIC in some form today? If so, be sure to leave a comment with your experiences and tips for those who might be interested in giving BASIC a shot, whether on desktop, retro systems or embedded :)

[Header Image: The HP 2000 system, mainly used for running time-shared BASIC, CC-BY 3.0]

Post a Comment