Know Audio: Stereo

In our occasional series charting audio and Hi-Fi technology we have passed at a technical level the main components of a home audio set-up. In our last outing when we looked at cabling we left you with a promise of covering instrumentation, but now it’s time instead for a short digression into another topic: stereo. It’s a word so tied-in with Hi-Fi that “a stereo” is an alternative word for almost any music system, but what does it really mean? What makes a stereo recording, and how does it arrive at your ears?

From West London Trains, To 3D Audio

As most of you will know, a mono recording uses a single microphone and a single channel while a stereo one uses two microphones recording simultaneously a left and right channel. These are then played back through a pair of speakers, and the result is a sense of spatial field for the listener. Instruments appear to come from their relative positions when recorded, and the sense of being in the performance is enhanced.

Stereo recording as we know it was first perfected as one of the many inventions credited to Alan Blumlein, then working for EMI in London. We have one of his stereo demonstration films in “Trains at Hayes“, filmed from the EMI laboratories overlooking the Great Western Railway, and featuring a series of steam-hauled trains crossing the field of view with a corresponding stereo sound field. His work laid down the fundamentals of stereo recording, including microphone configurations and what would become the standard for stereo audio recording on disk with the channels on the opposite sides of a 45 degree groove.

More Than Just A Mix

On the face of it, a stereo recording delivers only left-right positional information, and thus can be created from a series of mono tracks by adjusting their position in the stereo mix. For example, a band could have the bass guitar placed mostly in the left channel and the lead guitar in the right, with the drummer and vocalist equally in both channels to place them in the centre. Listen to “Yellow Submarine” fully panned.

In the modern era, a true stereo recording picks up much more than the relative intensities of different sounds, it records the complex web of timing and phase differences in the sound including those in the background noise. Thus a stereo recording created from a mix of mono recordings can best be referred to as pseudo-stereo because it lacks that phase information which gives the stereo recording so much depth.

In an analogue tape deck or a vinyl record the stereo channels are recorded separately as tape tracks or opposite sides of the groove. Meanwhile in digital audio systems the left and right channels arrive as bitstreams either from an interleaved i2S source such as a CD player, or from a decompression algorithm in for example an MP3 player or internet streaming software. There is however one place in which you’ll still commonly encounter a stereo source that uses an analogue encoding system, namely FM radio. This features a system in which the main broadcast is in mono, but the stereo information is separately encoded on the transmission at an inaudible frequency for decoding in the receiver.

The Last Bastion Of Analogue Stereo

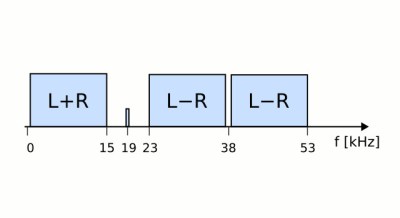

For the purposes of FM broadcasting, the left and right channels are combined into sum, or L+R that represents the mono component, and a difference between the channels, or L-R. These are quickly generated using a straightforward op-amp circuit. The L+R is modulated as the audio you hear on a mono receiver, while the L-R is encoded separately as a 38 kHz double sideband signal out of the audio range. A 19 khz pilot tone is added between the audio band and the stereo information, and in the demodulator this is used with a frequency doubler to provide a 38 kHz tone to demodulate the L-R difference component. This is then added and subtracted from the mono signal to rebuild the left and right channels. This system originated in a Zenith proposal from the early 1960s, and remains in use worldwide today.

There are a huge variety of signal processing techniques to enhance the stereo experience or produce stereo effects. Just one example is Dolby Atmos, and you will hear them at work in many computer games and films. All this digital magic is not the only way to play with stereo though, a favourite 1970s project was a stereo expander. These devices worked by subtracting a small amount of the left from the right and vice versa, having the effect of reducing the proportion of L+R and increasing the proportion of L-R in the output. In these days of cheap DSP, some professional audio is moving toward the similar Mid/Side encoding.

Binaural, It’s All In The Ears

There’s one final piece to the stereo puzzle, which you might have noticed if you’ve ever encountered a recording described as “binaural”. A stereo recording is generally intended to be played to the listener using a pair of speakers, in an ideal situation where the speakers and the listeners head form the points of an equilateral triangle. In this way each ear hears something of both left and right, with whichever side the ear is closest to being the dominant of the two.

In a binaural recording each channel is intended only for one ear, so it is designed to be listened to on a pair of headphones. Binaural recordings are often made with microphones designed to replicate the acoustic characteristics of a human head with microphones placed in its ear canals, with the intention of producing the illusion of a real-world directional audio field. YouTube is full of examples, and we’ve picked this traversal of central London to give you an idea.

So whether you’re an audio enthusiast or are satisfied with the cheapest of dollar-store speakers, we hope you’ve enjoyed our high-fidelity journey into the world of two-channel audio. Stay tuned for more, as we’ll return with another in this Know Audio series.

Post a Comment