Modern Wildfires And Their Effect On The Ozone Layer

The ozone layer is a precious thing, helping protect the Earth from the harshest of the sun’s radiative output. If anything were to damage this layer, we’d all feel the results in a very short order indeed.

In the past, humanity has worked to limit damage to the ozone layer from our own intentional actions. However, it’s not just aerosol cans and damaged air conditioning systems that are putting it at risk these days. The fierce wildfires we’ve seen so much of in recent years are also having a negative effect. Let’s take a look at why the ozone layer matters, and how it’s being affected by these wildfires.

A Protective Blanket

The fusion reactor that we call the Sun is a vicious thing. As it collides hydrogen atoms, mashing them together into helium, it releases a great deal of heat, light, and other electromagnetic radiation. Much of this radiation can be harmful to humans, plants, and other organisms.

Thankfully, the Earth has the ozone layer for protection. It’s a part of the atmosphere, or the stratosphere to be precise, that has a higher concentration of ozone than the rest of the atmosphere. The difference is actually quite slight – the ozone layer features the triple-atom oxygen molecule at a level of 10 parts per million (ppm), versus the level of 0.3 ppm seen on average in the rest of the atmosphere.

Those ten ozone molecules out of every million do an important job: blocking around 97-99% of the sun’s medium-frequency ultraviolet radiation. Without the ozone layer in place, we’d all sunburn far more quickly. In fact, if it was gone entirely, plants would struggle to photosynthesize, food supplies would dry up, and the surface of the Earth would essentially be sterilized in short order

The ozone layer is delicate, however. A wide variety of man-made chemicals, primarily CFCs, can break down ozone molecules, and have led to the commonly-known hole in the ozone layer which is still present to this day. Due to the crucial protective nature of the ozone layer, much work has gone into restricting the use of these chemicals and other measures to protect the ozone layer’s existence.

The Effect of Wildfires

The largest wildfires burn with such heat and intensity that they create huge plumes of smoke that can reach immense heights, even lofting smoke particles and combustion byproducts into the stratosphere. It’s a simple result of the fact that hot gases tend to rise up, and wildfires create plenty of those.

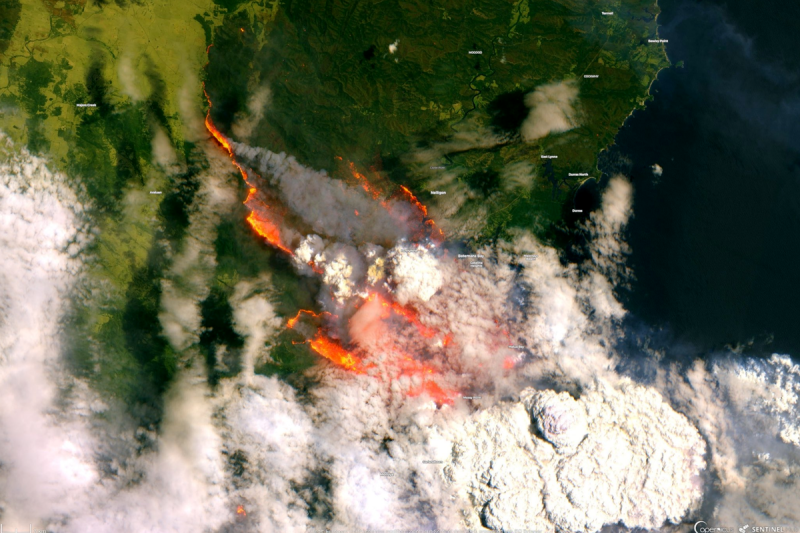

New research has now shown that these compounds can actually change the composition of gases in the upper atmosphere, and potentially even destroy ozone in this atmospheric layer. Scientists used the infrared spectrometer on the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment, a mission running on Canadian satellite SCISAT, to investigate the issue in the wake of Australia’s tragic 2019/2020 “Black Summer” fires.

Taking spectral measurements of the smoke particles in the upper atmosphere, it became clear that the particles contained oxygenated organic molecules, which could undergo chemical reactions with other molecules in the stratosphere. Further measurements noted increases in levels of molecules like formaldehyde, chlorine nitrate, chlorine monoxide, and hypochlorous acid. In turn, decreases in ozone levels were detected, as well as a drop in levels of nitrogen dioxide and hydrochloric acid.

Such major perturbations in the atmospheric chemistry being studied had not been observed in the previous 15 years of satellite measurements. There was a small initial bump to ozone levels after the wildfires, suspected to be due to similar reactions that create ozone pollution at ground level. However, from April to December 2020, ozone levels dropped precipitously to below the averages seen from 2005 to 2019.

Realistically, there’s not a lot that can be done to rectify this problem directly. Wildfires are already fought by those on the ground to protect life and limb, as well as property. Putting them out quicker would help, but fire crews are already doing everything they can in such cases.

It’s not all bad news for the ozone layer, however. Since the Montreal Protocol outlawed most production of CFC gases that harmed the ozone layer, we’ve seen gradual recovery from earlier human-induced damage. Despite recent spikes, the hole in the ozone layer is expected to close up within the next 50 years or so. In fact,when NASA checked in 2019, the hole in the ozone layer was the smallest its been since 1982. However, if major wildfires continue to occur with increasing severity, we may be in for more trouble.

In the end, reducing carbon emissions, and halting the pace of climate change is the best thing we can do to tackle this problem. Reducing global temperatures should help reduce the occurrence of wildfires, and their severity, and thus less smoke will be lofted into the upper atmosphere where it’s causing such a stir.

Headline image from the ESA’s Sentinel-2 satellite. ESA, Copernicus EMS via Twitter

Post a Comment