Ask Hackaday: Why Don’t Automakers Make Their Own EV Batteries?

Sales of electric vehicles continue to climb, topping three million cars worldwide last year. All these electric cars need batteries, of course, which means demand for rechargeable cells is through the roof.

All those cells have to come from somewhere, of course, and many are surprised to learn that automakers don’t manufacture EV batteries themselves. Instead, they’re typically sourced from outside suppliers. Today, you get to Ask Hackaday: why aren’t EV batteries manufactured by the automakers themselves?

Experience and Infrastructure

Automotive manufacturers actually outsource the development and production of many components of their vehicles. Your car rides on tires from companies like Bridgestone, Goodyear, and Falken, not Ford, Dodge, or Volkswagen. Similarly, FOX shocks are prized in off-road trucks like the Ford F-150 Raptor, and if you dig into your fuel management system, many of the pumps and sensors are probably made by Bosch.

The fact is, automakers don’t have the capacity to design and manufacture every single little component of their cars. Doing so would rarely make sense, either. Take oxygen sensors, for example. These delicate electronic components are complicated to manufacture, and require specific expertise. Any automaker designing their own would have to cover the full cost of R&D, and economies of scale would be limited by their own vehicle output. However, pretty much every car needs an oxygen sensor, so an outside company that supplies many automakers has an advantage. Their economies of scale are much larger, as they can offset R&D costs across millions of units sold to equip vehicles made by several different manufacturers.

Furthermore, automakers were not in the business of producing batteries by the time electric cars started to hit the market en masse. Starting a battery manufacturing effort from scratch is no mean feat, and would only have added to the difficulty of bringing an electric vehicle to market. Simply purchasing working batteries from an experienced supplier eliminates a whole lot of work, and most automakers have taken this path thus far. Even Tesla has gone this way, sourcing batteries from Panasonic and CATL among other companies over the years. Indeed, Panasonic invested heavily in Tesla’s Gigafactory, and runs much of the production equipment there.

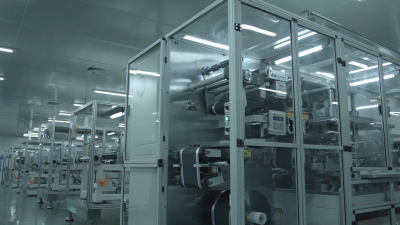

Specialist battery manufacturers have the benefit of decades of experience in both battery chemistry, as well as the fundamentals of manufacturing cells. Batteries are delicate things, and getting their construction even slightly wrong can lead to dangerous fires. Scaling up production is difficult too, and with EVs often requiring hundreds or thousands of cells, monumental effort is required in this regard.

Thus, when it came time to produce electric vehicles, automakers had a choice. They could purchase cells from existing suppliers, with a known-good product and production lines ready to go. Or, they could start building their own factories, hiring battery experts, and begin the process of manufacturing their own cells. The latter route is fraught with hurdles, and requires years of effort to get a usable product available in real numbers. The former choice gets batteries in cars practically from Day 1. For automakers, the decision was easy.

What Could Go Wrong?

Even the experts get it wrong sometimes, of course. The current Chevrolet Bolt uses cells sourced from supplier LG Chem. Torn anode tabs and folded separator materials in some cells lead to battery fires that destroyed several cars and prompted a huge recall effort. Over 140,000 cars have been recalled, causing brand damage and a huge headache for General Motors. However, as the fault was with the battery supplier, GM were able to point the finger outside, and LG agreed to pay $1.9 billion to cover the costs of rectifying the problem.

Thus, for a whole host of reasons, automakers typically source their batteries from external manufacturers. Car companies didn’t have the knowledge in house to make their own cells, nor did they have the factories to produce them en masse. Sourcing them outside also often provides a cheaper product with R&D costs essentially amortized across several customers. It also means that automakers were able to get to market sooner, and also provided companies with an opportunity for restitution if they were inadvertently supplied with poor product.

There are drawbacks, of course. Doing battery research and production in-house can net competitive advantages. If, for example, a company unlocks the secret to a new battery chemistry, they could produce cars with longer range and more performance than their rivals. However, it’s a risky game with no guarantee of success, and it can take many years to go from a successful lab-built cell to batteries that are ready for automotive use. Then, there’s the sticky problem of kitting out a factory to churn out millions of your special cells a year.

Winds of Change

Competition in the automotive world has been fairly level for some time, with emissions regulations and mature engine technology meaning that no one automaker had any wild advantage over another. However, being the only company with access to a new class of battery could be an absolute gamechanger. It’s easy to visualize now—imagine if only one company had access to lithium cells, while everyone else was stuck with nickel metal hydride technology. Cars with lithium batteries now have ranges that can exceed 400 miles. A car built with NiMH cells would be lucky to have a third of that, while being heavier and unable to deliver anywhere near as much current for hard acceleration.

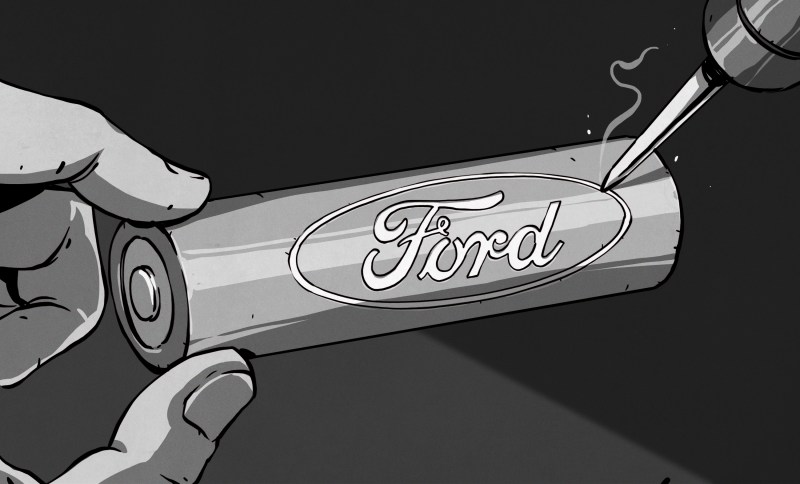

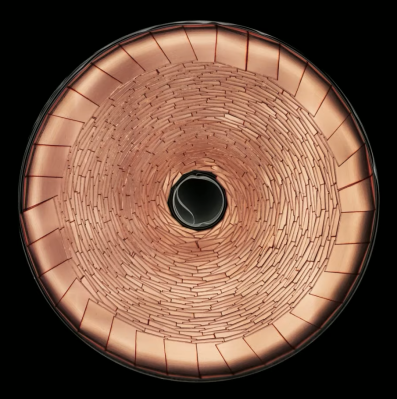

Tesla are starting to look into vertical integration by producing their new tabless cells in-house, a step that it took after over a decade in the EV industry. BMW are doing much the same, investing deeply into solid-state batteries. These technologies could provide range gains in the double-digit percentages, and if built by the automakers themselves, could be unavailable to rivals, providing a major advantage in the marketplace.

As automakers grow more familiar with electric vehicle technology, expect more players to make steps towards producing their own batteries. However, others will continue to see the value in partnerships with established players, investing in new technologies and production capacity at arms length. There’s no one right way in business, of course, but there are always plenty of wrong ones. Traditionally-conservative auto companies will tread carefully as always, while hot upstarts like Tesla will be the ones making the drastic moves.

Post a Comment