History of Closed Captions: Entering the Digital Era

When you want to read what is being said on a television program, movie, or video you turn on the captions. Looking under the hood to see how this text is delivered is a fascinating story that stared with a technology called Closed Captions, and extended into another called Subtitles (which is arguably the older technology).

I covered the difference between the two, and their backstory, in my previous article on the analog era of closed captions. Today I want to jump into another fascinating chapter of the story: what happened to closed captions as the digital age took over? From peculiar implementations on disc media to esoteric decoding hardware and a baffling quirk of HDMI, it’s a fantastic story.

There were some great questions in the comments section from last time, hopefully I have answered most of these here. Let’s start with some of the off-label uses of closed captioning and Vertical Blanking Interval (VBI) data.

Unintended Uses of VBI Data

While I was immersed in the world of VBI data and closed captions for several years, I kept discovering applications that were not related to the intended use.

Newsroom channel monitors

Back in the day, I discovered a small company called SoftTouch, Inc., “innovators in the obsolete” according to owner Doug Byrd. They made various niche market CC products, and in fact, I still have several of his products today. Most prized are two CCEPlus line 21 generator cards, the only full-length ISA cards I’ve ever owned, which have given me an excuse to keep a fully working Gateway 2000 486DX2-66V in my lab for over 15 years.

I enjoyed my phone calls with Doug over the years. He is quite a character, a great story teller, and I learned a lot about the captioning industry from him. While his niche products were used in all kinds of systems, one that sticks in my mind is in news rooms. Imagine a system designed to monitor a wall of televisions (or just tuners) equipped with CC decoders feeding the RS-232 text to a computer which is programmed to look for various key words and alert the staff when found. In fact, we wrote about a similar project on Hackaday about ten years ago.

Real-time translating from Spanish

One surprising application I stumbled upon was a small set top box designed to translate the English dialogue for Spanish speakers who liked to watch US daytime soap operas. This was an interesting project on two fronts. Researchers Fred Popowich and Paul McFetridge at Simon Fraser University developed a “shake and bake” machine translation algorithm which could be implemented in hardware of the day. It was about 80% accurate, but they discovered something interesting. Eighty percent worked just fine for people who only spoke Spanish, but bilingual speakers were annoyed by the mistakes.

Dictionary lookups from DVD captioning

I was discussing closed captioning and DVD subtitles with some Korean engineer friends one night over soju, and learned there was a Korean company who made a specialized DVD player. What made this player special was it had a built-in OCR engine to read the subtitles (not the captions) and offer translations and definitions to the user — it was intended as a language educational product. It did not do real-time OCR translations, instead doing the OCR when the user pressed PAUSE in order to query the machine for help.

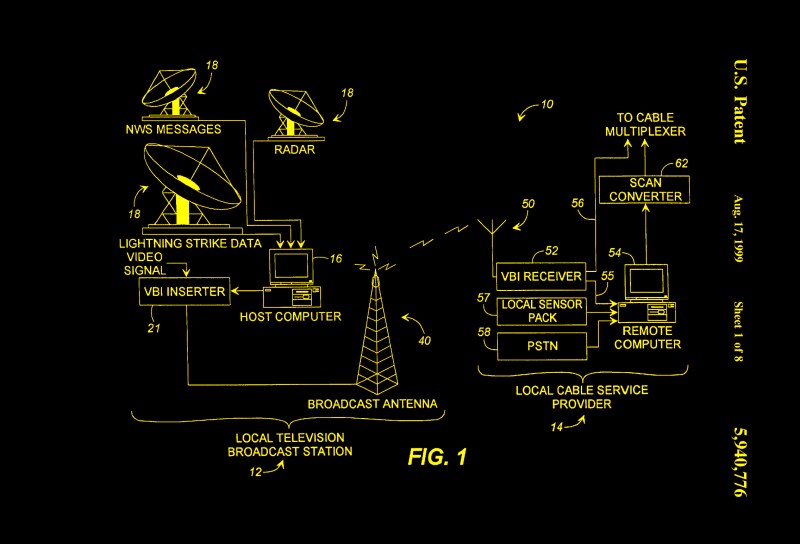

Weather radar data distribution

While teletext was primarily used in Europe, the WST standard included a variation for NTSC countries — The North American Broadcast Teletext Specification (NABTS) known also as EIA-516. Both CBS and NBC experimented with teletext service, but it wasn’t popular. However, the data broadcasting ability did find some traction in other ways. I discovered one surprising application while learning about VBI signals back in the early 2000s. I was talking to an engineer at a local weather radar company in the US, and found out they were broadcasting weather data and radar images over the VBI for the benefit of various emergency preparedness groups. He even lent me an NABTS receiver which I installed in my PC and could monitor the real time data from my desk. To my surprise, he told me that television stations were renting out the VBI lines. In crowded markets like New York City, for example, there might not even be any empty lines available.

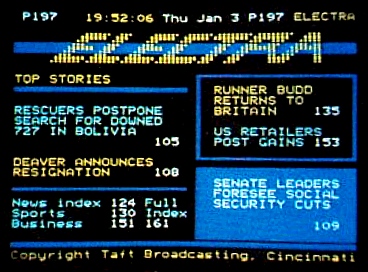

Financial Data

It wasn’t just the weather radar data folks using the VBI, either. A number of datacasting services sprang up which used the VBI to distribute financial information such as stock and commodity prices. Several networks were in operation, some since the late 1970s. They included DTN Real Time, Electra, and Tempo Text. By the mid 1990s, all these services had shut down, the internet having taken over the role of time-sensitive datacaster.

Extended Data Services

The closed caption standard was eventually amended to include what’s called extended data services, or XDS. This auxiliary data was carried in the field 2 VBI and included information like time of day, V-chip rating, station ID, and basic programming information. Some early electronic program guides (EPGs) like Guide Plus were sent over the VBI. There was also an emergency alerts portion of the XDS, which could announce all kinds of weather and other emergencies, down to the state and county region, and for a specified duration.

Making a Line 21 Decoder Today

As I mentioned in my article on analog closed captions, making an analog closed caption decoder in the 21st century is best done without relying on specialized all-in-one ICs. There are three functions required in such a receiver:

- Syncing to the video signal

- Slicing / thresholding the data

- Processing the protocol

Surprisingly, syncing to the incoming video was a real challenge. It was because of the Macrovision copy protection scheme. Wild pulses are inserted in the VBI, ostensibly to prevent making a tape recording (these pulses mess up the VCR’s AGC circuitry). Of course, people who want to make copies just built or bought a Macrovision suppression box. But if you want to reliably sync to Macrovision-ladened video, it’s not simple.

I considered making my own, but there are a lot of special cases. There were also some legal considerations at play, but I was in touch with the Macrovision engineers and wasn’t too worried about that. In the end, I went with a sync separator that was Macrovision tolerant, and had been designed and tested to work in a much wider variety of Macrovision scenarios than I could hope to reproduce in my testing.

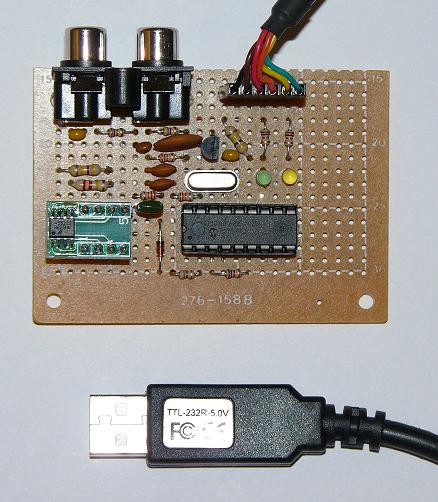

There are various ways to slice the line 21 data. I successfully built several boards based upon a clever open source project. Richard Ottosen and Eric Smith published a nice design using a Microchip PIC16F628, which was subsequently expanded on by Kevin Timmerman. These designs make good use of the PIC’s internal comparators: one as a peak detector and the other for data thresholding. Check these out if you are interested in making your own decoder.

Processing the data once you get it from the decoder can be hairy, depending on how accurate you want your design to be. Reader [unwiredben] commented on the previous article how fun it was to recently write a ground-up implementation. I wholeheartedly agree. One issue is that the requirements are spread out among various documents. Some of them were almost unobtainable back in the year 2000, and yet they make up the official, legal requirements expressed in the FCC regulations.

I particularly remember having a very tough time getting a required report from PBS and another from the National Captioning Institute. It wasn’t because they weren’t cooperative, but because the reports were so old they couldn’t find them. (I eventually got the reports, and also a real Telecaption II caption decoder on which many of the final specifications were based.)

One incident I recall is trying to buy a set of CC verification tapes. Supposedly they were available from WGBH Boston, but when I called it seemed that nobody had asked for them in years, and they weren’t sure any existed anymore. They eventually found one remaining set and shipped it to me here in Korea, where it almost got destroyed in customs due to some obscure law prohibiting the import of prerecorded media. One point to consider — if you simply want to extract text for analysis, the processing will be a lot easier than if you also want to properly display and position the text on-screen.

It is possible to build a digital CEA-708 (see below) decoder. If this is something you’re interested in,

The Making of Captions

The process of making the caption text is too complicated to cover here. In brief, the dialogue has to be transcribed into digital format. In the case of real-time captions like for news or sporting events, techniques, skills, and equipment have been brought over from the world of court reporters. In the case of pre-recorded programs, the process can be aided by scripts. But they still have to be checked against what was really said by the actors. Next, any additional cues are added, and then the dialogue has to be broken up into chunks which need to be correctly positioned on-screen and timed with the audio track.

If you’re interested in learning more about this, check out Gary Robson’s website. Not only does he discusses the process of making captions, but Gary has been in the caption industry for a long time and written several excellent books on the subject. I’ve read all of them and sought his advice on a few occasions — a very nice and knowledgeable guy.

Captions and Digital Video

So far the focus has been on analog closed captioning which was used for over-the-air broadcasting, and more or less for cable television broadcasts as well. But what about other ways we view programs? In the case of VHS tapes, it was fortunate, if not anticipated by the designers, that line 21 signals could easily be recorded and played back by videotape equipment. Then along comes digital video in formats like Laser Disc, DVDs, Blu-ray Discs, and streaming, and the world of captioning falls apart — for awhile, at least.

Transition to Digital

First we have the Laser Disc. They stored and played back captions in both NTSC and PAL formats. No big issues here, but just wait. Next comes the Digital Versatile Disc (DVD), and things begin to get murky for closed captioning — a situation that persists more or less to this day with DVD and Blu-ray Discs (BD). The DVD specification calls out a user data packet specifically to store the digital pairs of caption data (as digital data, not encoded in a video line). Although I’m not aware of any technical reason why a PAL DVD couldn’t do the same, only Region 1 (North America) NTSC discs can store the caption data and still be compliant with the specifications.

Most DVD players use this data to generate an analog line 21 signal on the video output signal(s), which can then be decoded by your TV set’s internal CC decoder under viewer control.

- Composite video output

- S-Video output:

- on the Y/Luma signal

- Component video output:

- on the Green/Sync signal if RGB

- on the Y-channel if Y/Pb/Pr

There are a very few players that can actually decode the caption data and overlay this onto the output video as open captions, but these players are the exception rather than the norm.

We Have a Problem…

You may see where this is leading — there is a hidden assumption with Line 21 closed captions. By definition, they are only defined to exist on interlaced standard definition video (480i in the case of NTSC). While there is no technical reason not to, there isn’t any agreed upon standard to send the data over the VBI for any other video timing. Nobody thought about it back in the 1970s.

This led to upset consumers who purchased HD televisions and DVD or BD players, only to find out that they couldn’t view the closed caption data unless they watched the program in 480i mode. But still, if you use closed captions, live within NTSC DVD Region 1, and are content to watch programming in 480i standard mode. Everything is good? Not quite.

For some reason I still don’t understand, not all pre-recorded DVDs contained closed captions, even if captions existed for the movie and were available on VHS tape releases by the same studio. This seemed to be random with one exception — Universal Studio DVDs never had closed captions. Don’t worry, DVD technology offered a “new” solution to this problem — subtitles. Remember those from the early 1900s?

Because everything was now digital, DVDs and BDs could offer the old style hard-baked subtitles, but with a twist. The user could turn them on and off, and could often select from a wider variety of languages (CC was typically limited to two languages, if that, and those from a narrow choice of languages). The freedom to design subtitles was almost boundless — as they were just pictures with a transparent background, they could contain anything. It wasn’t uncommon to see both English and English CC subtitles on some discs.

Despite lots of sources claiming the contrary, BD discs can and do carry line 21 captioning. I have used BD and BD players for testing line 21 signals over the past ten years with no issues. But the catch is the same as with with DVD, they are only generated at 480i standard definition analog outputs. And the dearth of captioned discs is even worse than DVD — I would estimate that less than one third of BDs have captioning. I mentioned above very few DVDs have internal CC decoders. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a BD player with one.

Digital Television

The industry working group responsible for closed caption standards realized something needed to be done to bring captioning into the digital era. The group developed a new version of closed captioning, addressing many of the concerns of the community of analog captioning users. Recall that the analog standard was EIA-608. The new standard is called CEA-708 (CEA was spun out of the EIA when it closed down in 2011). Some features that were added, aside from a format that was compatible with ATSC digital broadcasting, include:

- true multi-language support

- different font sizes

- different font styles

- can be repositioned on-screen

- legacy EIA-608 capability

As digital television broadcasts became the norm, TV sets were replaced with those capable of decoding the new 708 style captions. Your TV set probably has this ability today.

Baseband Digital Video and Captions

The quality of our TV and monitor displays increased rapidly. HD analog component signals were soon replaced by high speed, digital differential signalling. Various standards exist, but HDMI has become the de-facto digital video interface for consumer video. Our television sets are receiving HD digital programming and are able to decode and display new style captions. All is right with the world. Well, not so fast.

One would surely expect a brand new standard such as HDMI, designed from the ground up to support all current and conceivable kinds of communications between consumer A/V devices, to handle the trivial bandwidth and format of the closed captioning signal. Well, you’d be disappointed — somebody did not get the memo. From the start, HDMI has not carried the closed captioning signal. One could be forgiven for thinking it was an intentional decision, as the standard has been updated numerous times and HDMI cables still can’t carry closed captioning.

One would surely expect a brand new standard such as HDMI, designed from the ground up to support all current and conceivable kinds of communications between consumer A/V devices, to handle the trivial bandwidth and format of the closed captioning signal. Well, you’d be disappointed — somebody did not get the memo. From the start, HDMI has not carried the closed captioning signal. One could be forgiven for thinking it was an intentional decision, as the standard has been updated numerous times and HDMI cables still can’t carry closed captioning.

The explanation from the industry was that with change to digital meant that caption decoding must now be performed in your set-top box. This might not have been too bad of a choice if these boxes also provided an ATSC-modulated RF channel output with EIA-708 captions, akin to the Ch 2/3 outputs of old computers and VHS players. As it is, consumers who rely on closed captions now have two or more decoders to fool with: one in the TV’s HD digital receiver, one in a cable set-top box, and perhaps a third in their DVD/BD player.

FCC Saves the Day?

With the shift from prerecorded media to streaming, the situation really got out of hand. The FCC stepped in and solved the situation, kind of. You might think that with a well established, existing standard like EIA-708, something already being used in TV sets and mandated by the FCC for all broadcasters, the reasonable answer would be to require streaming services to use EIA-708 also. And maybe encourage the HDMI organization to carry closed captioning information as well. Alas, that was not the decision. Instead, the FCC ruled that streaming services can use any captioning technology standard they wish, as long as they can deliver captions.

I feel that this state of affairs is less than ideal. Looking back at all the neat and unintended uses of analog closed captions, I wonder how many novel innovations are we missing out on by this lack of a uniform captioning standard. Or rather, our intentional decision not to apply the existing captioning standard uniformly. That said, I don’t want my grumbling about technical details to distract us from the big picture here. The true goal of these regulations, providing captions to the deaf and hard of hearing community, is being applied across all methods of program delivery. That’s wonderful, indeed.

Post a Comment