NASA Selects SpaceX to Launch Lunar Gateway

While not a Cabinet position, the NASA Administrator is nominated by the president of the United States and tasked with enacting their overall space policy. As such, a new occupant in the White House has historically resulted in a different long-term directive for the agency. Some presidents have wanted bold programs of exploration, while others have directed NASA to follow a more reserved and economical path, with the largest shifts traditionally happening when the administration changes hands between the parties.

So it’s no surprise that the fate of Artemis, a bold program initiated by the previous administration that aims to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon, has been considered uncertain since the November election. But the recent announcement that SpaceX has been awarded a $331.8 million contract to launch the first two modules of the lunar Gateway station, an orbital outpost that will serve as a rallying point for astronauts coming and going to the Moon’s surface, should help quell some concerns. While the components still aren’t slated to fly until 2024 at the earliest, it’s a step in the right direction and strong indicator that the new administration plans on seeing Artemis through.

Two For the Price of One

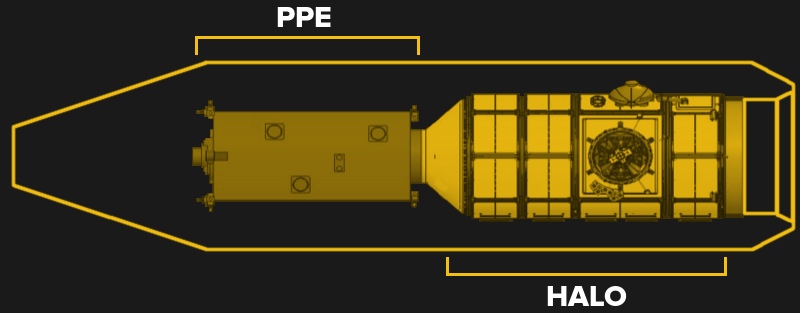

The contracted launch is unique in that SpaceX is being tasked with launching two separate modules, the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) built by Maxar Technologies, and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) from Northrop Grumman, on the same rocket. These two core Gateway components, which essentially make up a miniature space station themselves, will be mated on the ground at Kennedy Space Center and tested for several months before being loaded onto a Falcon Heavy.

While the mass of these two modules is well within the capabilities of the Falcon Heavy, their combined length will require SpaceX to develop an extended payload fairing. They will also need to build a new mobile gantry at launchpad 39A that will allow for the modules to be attached to the rocket vertically, rather than horizontally as is the case with all current Falcon and Falcon Heavy launches. The new fairing and integration facility naturally represent a considerable investment by SpaceX, but long term, these changes will enable the Falcon Heavy to carry large national security satellites for the Pentagon and provide the company with a lucrative new revenue stream.

Originally the PPE and HALO modules would have flown on two separate rockets, possibly even by different launch providers, needing an autonomous docking maneuver after their rendezvous at the Moon. But to reduce costs and get the Gateway operational sooner, it was decided to send them both at the same time. This does introduce the possibility that a failure could result in the loss of both modules, but since their functionality is so intrinsically linked anyway, NASA believes it’s worth the risk to expedite the program.

Deep Space Legacy

As with many NASA projects, Gateway is the end result of a long and winding development process. The PPE is an evolution of the electric propulsion module intended for the agency’s now-canceled Asteroid Redirect Mission, and the idea of a small self-contained space station being sent to lunar orbit has its roots in the Deep Space Habitat concept that engineers have been working on since the retirement of the Shuttle refocused NASA’s long-term goals on activities outside of low Earth orbit.

Back in 2017, NASA was calling this concept the Deep Space Gateway, and envisioned it as a stepping stone to distant destinations such as Mars. The three initial modules of the Deep Space Gateway would be launched into orbit around the Moon using the upgraded Block 1B variant of the Space Launch System. In this configuration, the booster would use the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) and have enough power to carry a station module and Orion crew capsule in one launch. At that point, commercial launches were only being considered for less critical components which would be added on later, such as an airlock or additional laboratory module.

But the EUS, much like the Space Launch System itself, is taking far longer to bring online than anyone at NASA anticipated. Despite being in development since 2014, the design only made it through the final review stage a few months ago, and actual flight hardware isn’t expected to be completed until at least 2025. This would put it beyond all the currently scheduled Artemis missions, though if everything goes according to plan, by that time both Gateway and a potential outpost on the lunar surface will be able to benefit from the enhanced cargo capabilities of the SLS.

Competition, or Lack Thereof

Launching large objects to the Moon and Mars is arguably why NASA is building their Space Launch System in the first place, and yet according to the current timeline, Gateway will be up and operational before the megarocket is capable of delivering any noteworthy amount of cargo. Much like the recent announcement that NASA will fly the Europa Clipper on a commercial booster, this is another example of the agency’s homegrown vehicle losing a high profile mission to a smaller and cheaper rocket.

At this point, one of the few clear uses for the Space Launch System and its EUS in the context of the Artemis program is for delivering large landers to the Moon. Whether they go directly into lunar orbit or rendezvous with the Gateway, two out of the three commercial Human Landing Systems selected by NASA are designed to be launched aboard an SLS Block 1B. Although as a contingency, their principle components can also be carried on smaller rockets and assembled in orbit.

But the third lander, proposed by SpaceX, is a variant of their Starship vehicle that can take off from Earth and land on the Moon under its own power. As a completely independent system, it doesn’t require the Gateway or SLS to complete its mission. On one hand, this is a clear advantage given how frequently NASA’s own plans miss their deadlines and slip further into the future. But there’s certainly an argument to be made against pinning so much of the Artemis program on a single contractor.

A long-term sustainable program for lunar exploration and utilization should include a fleet of boosters and spacecraft that are independently designed, manufactured, and operated. Yet as of right now, SpaceX is the sole company responsible for both launching Gateway and sending regular resupply missions to it. Whether it’s Old Space or New Space, there’s an inherent risk in relying so completely on any one entity. But unless something changes in the next few years, it looks like that’s exactly the situation NASA’s Artemis program could find itself in.

Post a Comment