Why Fedora Decided to Give CC0 Licensed Code the Boot

The term “open source” can be tricky. For many people, it’s taken to mean that a particular piece of software is free and that they can do whatever they wish with it. But the reality is far more complex, and the actual rights you’re afforded as the user depend entirely on which license the developers chose to release their code under. Open source code can cost money, open source code can place limits on how you use it, and in some cases, open source code can even get you into trouble down the line.

Which is precisely what the Fedora Project is looking to avoid with their recent decision to reject all code licensed under the Creative Common’s “Public Domain Dedication” CC0 license. It will still be allowed for content such as artwork, and there may even be exceptions made for existing packages on a case-by-case basis, but CC0 will soon be stricken from the list of accepted code licenses for all new submissions.

Fedora turning their nose up at a software license wouldn’t normally be newsworthy. In fact, there’s a fairly long list of licenses that the project deems unacceptable for inclusion. The surprising part here is that CC0 was once an accepted license, and is just now being reclassified due to an evolving mindset within the larger free and open source (FOSS) community.

Fedora turning their nose up at a software license wouldn’t normally be newsworthy. In fact, there’s a fairly long list of licenses that the project deems unacceptable for inclusion. The surprising part here is that CC0 was once an accepted license, and is just now being reclassified due to an evolving mindset within the larger free and open source (FOSS) community.

So what’s the problem with CC0 that’s convinced Fedora to distance themselves from it, and does this mean you shouldn’t be using the license for your own projects?

The Right Tool for the Job

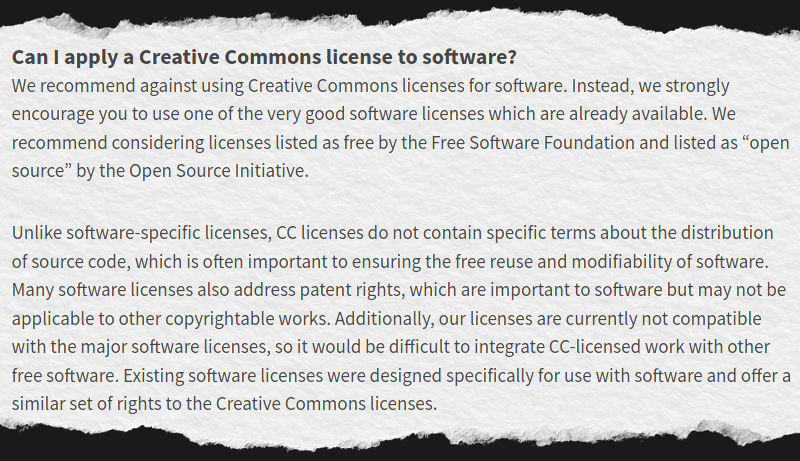

Those familiar with the Creative Commons and their family of licenses may find the most surprisingly element of this story is that the Fedora Project once accepted CC0 for software in the first place. After all, the intent was always to create a series of licenses specifically for creative works. The goal of the organization and its licenses is literally right in the name.

A successor of the earlier Open Content Project, Creative Commons was founded in 2001 to “overcome legal obstacles to the sharing of knowledge and creativity” by providing a free framework by which individuals and organizations could release things such as music, artwork, or educational material. But software was never part of the equation. Why would it be? Seminal software licenses such as the GNU General Public License and the MIT License had already been available for over a decade at that point.

To avoid any ambiguity the Creative Commons even addresses the issue in their FAQ, making it clear that not only are their licenses not a good choice for software, but that better options already exist:

The Patent Trap

If an organization goes out of their way to tell you that what they have developed is not fit for a particular purpose, it seems to go without saying that you should probably take their word for it. The Creative Commons FAQ outlines several excellent reasons their licenses shouldn’t be used for software, but among them, there is one that particularly stands out for users like the Fedora Project — patent rights.

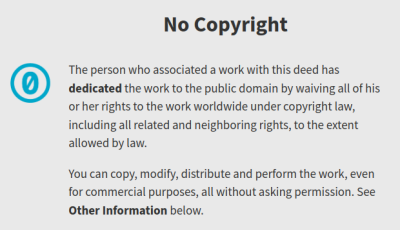

This might seem counterintuitive, since the CC0 license is intended for public domain works and clearly states that the creator is “waiving all of his or her rights to the work worldwide under copyright law” by using it. But the problem is that patents aren’t covered by copyright law. In fact, a look at the full-text version of the license shows that CC0 contains a troubling clause under “Limitations and Disclaimers” that addresses this specifically: “No trademark or patent rights held by Affirmer are waived, abandoned, surrendered, licensed or otherwise affected by this document.”

In other words, while the creator may be willing to give up the copyright to whatever has been licensed under CC0, they are still free to patent it. More troubling, they still reserve the right to leverage that patent however they see fit. Theoretically, that means the developer who originally released a piece of source code under CC0 could later claim that anyone who used the code was infringing on their patent, and potentially demand royalties.

Playing With Fire

It’s pretty clear why the Fedora Project would be worried about something like this. Imagine a piece of CC0 licensed code gets merged with one of the system’s core packages, and ends up being distributed to millions of users. Suddenly the original developer emerges from the shadows, claims patent infringement, and demands compensation. Could Fedora’s lawyers, or more likely Red Hat’s, beat such a claim? Maybe. Is using CC0 code worth running the risk of finding out for sure? Not a chance.

It’s worth mentioning that this is by no means a new concern. In fact, the patent clause is what kept the Open Source Initiative’s (OSI) License Review Committee from being able to conclusively determine if CC0 actually met their definition of an open source license back in 2012. The Committee couldn’t reach consensus, as members were concerned that putting such language in a software license would set a dangerous precedent. Given its tumultuous history, Fedora’s decision to ever accept CC0 in the first place is even more perplexing.

But what does that mean for the individual hacker? Should you use CC0 for your own projects? It depends on what you’re looking to accomplish. CC0 is fine choice if you want to give away a creative work (such as a song, poem, or piece of art) and aren’t concerned about what happens with it in the future, but according to Creative Common’s own documentation, it simply wasn’t designed with the unique aspects of software licensing in mind.

A better question might be, should you use CC0 code that you find floating around on the Internet? The answer to that is more nuanced, but given everything we’ve just gone over, one must wonder what kind of developer would still chose to use it. Unless you’re prepared to deal with the consequences of finding out, I’d suggest you leave it alone.

Post a Comment