Sea Level Rise From Melting Ice Sheets Could Soon Be Locked In

Where today we talk broadly of climate change and it’s various effects, the conversation was once simpler. We called it “global warming” and fretted about cooking outside in the summer and the sea level rise that would claim so many of our favorite cities.

Scientists are now concerned that sea level rises could be locked in, as ice sheets and glaciers pass “tipping points” beyond which their loss cannot be stopped. Research is ongoing to determine how best we can avoid these points of no return.

Ice, Ice, Baby

The threat of sea level rise due to melting ice is often discounted by climate change sceptics. The common citation is that a floating ice cube doesn’t change the water level as it melts, due to the principle of displacement. However, this doesn’t account for the fact that much of the ice in the Antarctic actually sits atop land. When this ice melts, it directly leads to sea level rise of a potentially drastic scale.

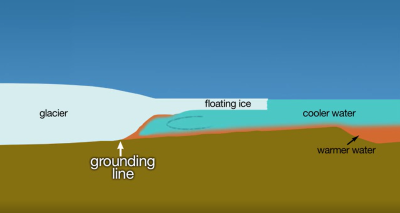

Of prime concern is the Thwaites Glacier, which scientists have nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier” for the perceived danger it poses. The glacier is held back, particularly in the east, by a large floating ice shelf. This slows the flow of the glacier and helps keep it stable. The floating ice shelf is further aided in this task as it sits against a large underwater mountain, acting as a brace.

Recently, scientists have noted that the floating ice shelf is showing worrying signs of deterioration. Large cracks have been spiderwebbing across the ice, prompting concerns for the long-term stability of the shelf. The effect is similar to cracks in a window; once they reach a certain point, the entire glass just shatters. Compounding the problem, the ice shelf appears to be losing its grip on the underwater mountain holding it in place as warmer waters melt the sheet from below.

The Thwaites Glacier is already responsible for about 4% of global sea level rise each year. The concern is that with the loss of the floating ice shelf, the glacier could increase its flows towards the ocean, increasing up to 5% of sea level rise in the short term alone. Scientists currently expect the ice shelf to break up within the next 5 years or so.

The longer-term implications are profound, if uncertain at this stage. If the broader Thwaites Glacier breaks up and melts away, a process scientists expect could happen in as little as a few centuries, it would contribute a 65 centimeter rise to global sea levels. If the broader West Antarctic Ice Sheet were lost, it would add 3.3 meters to global sea levels, completely changing the world map.

We Prefer Greenland Icy, Not Green

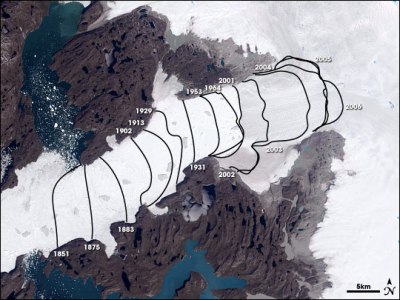

It’s not just a problem in the Southern Hemisphere, either. Scientists believe that 1-2 meters of sea level rise may be locked in from glaciers in Greenland that seem set to melt regardless of what we do now. 140 years of records regarding ice-sheet height and the rates of glacial melting in the Jakobshavn basin indicate that there may be a feedback effect that causes rapid ice loss. As the ice sheet thins, it is more exposed to warmer air at lower altitudes, accelerating the effect.

The melting ice is also playing havoc with ocean circulation, too. The cooler waters from the melting Greenland ice are slowing currents responsible for transporting heat through the oceans around the world. Fears are that this could disrupt rainfall over crucial areas, create more droughts, and warm the southern oceans, further accelerating the melt of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

There is some solace to be had in the time scale of the melt predicted, for currently-living humans at least. It’s expected that the 1-2 meter rise from the Jakobshavn melt would take a few centuries to progress, even if we can’t stop it now. It’s also not certain that a tipping point has been passed, however, with global temperatures and greenhouse gas concentrations still rising, that point may be moot. Regardless, lacking a return to pre-industrial temperatures, researchers believe that significant ice loss, and corresponding sea level rise, is almost a certainty.

The most harrowing predictions suggest that the loss of Greenland’s ice sheets could be locked in at 1.5 °C of warming, which could be reached as soon as 2030. If the models are correct, once this point is reached, reducing emissions and stabilizing global temperatures would not be enough to rescue the ice sheet, which would continue to melt and raise sea levels slowly over a long period of time.

Future Outlook

Taken in isolation, neither glacier presents an immediate threat to our coastal cities in the next decade. However, if multiple climate systems continue being pushed beyond points of no return, as we’ve explored before, we may end up locking in significant negative changes before we’re capable of dropping emissions and stabilizing the climate.

[Banner image: “Surprise Glacier” by USGS. Thumbnail: Calving at Perito Moreno by NASA Goddard.]

Post a Comment