Remoticon 2021 // Rob Weinstein Builds an HP-35 from the Patent Up

Fifty years ago, Hewlett-Packard introduced the first handheld scientific calculator, the HP-35. It was quite the engineering feat, since equivalent machines of the day were bulky desktop affairs, if not rack-mounted. [Rob Weinstein] has long been a fan of HP calculators, and used an HP-41C for many years until it wore out. Since then he gradually developed a curiosity about these old calculators and what made them tick. The more he read, the more engrossed he became. [Rob] eventually decided to embark on a three year long reverse-engineer journey that culminated a recreation of the original design on a protoboard that operates exactly like the original from 1972 (although not quite pocket-sized). In this presentation he walks us through the history of the calculator design and his efforts in understanding and eventually replicating it using modern FPGAs.

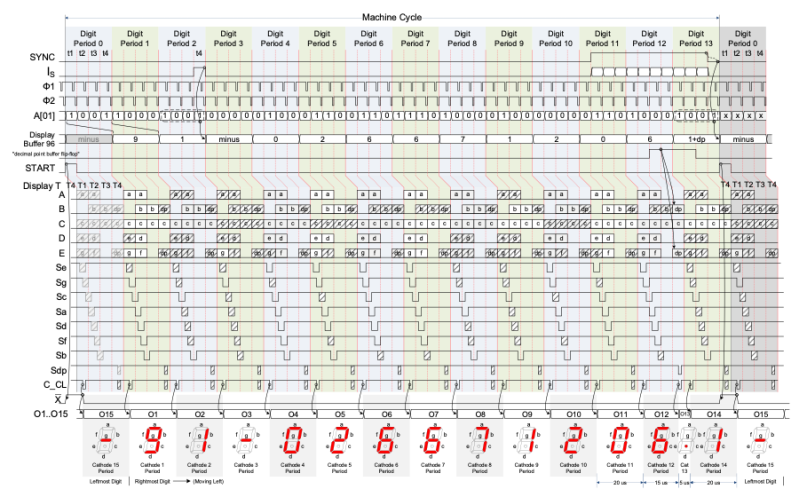

The HP patent ( US Patent 4,001,569 ) contains an extremely detailed explanation of the calculator in nearly every aspect. There are many novel concepts in the design, and [Rob] delves into two of them in his presentation. Early LED devices were a drain on batteries, and HP engineers came up with a clever solution. In a complex orchestra of multiplexed switches, they steered current through inductors and LED segments, storing energy temporarily and eliminating the need for inefficient dropping resistors. But even more complicated is the serial processor architecture of the calculator. The first microprocessors were not available when HP started this design, so the entire processor was done at the gate level. Everything operates on 56-bit registers which are constantly circulating around in circular shift registers. [Rob] has really done his homework here, carefully studying each section of the design in great depth, drawing upon old documents and books when available, and making his own material when not. For example, in the course of figuring everything out, [Rob] prepared 338 pages of timing charts in addition to those in the patent.

One section called the “Micro-Programmed Controller” is presented as just a black-box in the patent. This is the heart of the systems, and is essential to the calculator’s operation. However, all the other parts that talk to the controller were so well-described in the patent that [Rob] was able to back out the details. The controller, and all sections of the calculator, was implemented in Verilog, and tested on an instrumented workbench he built to test each module.

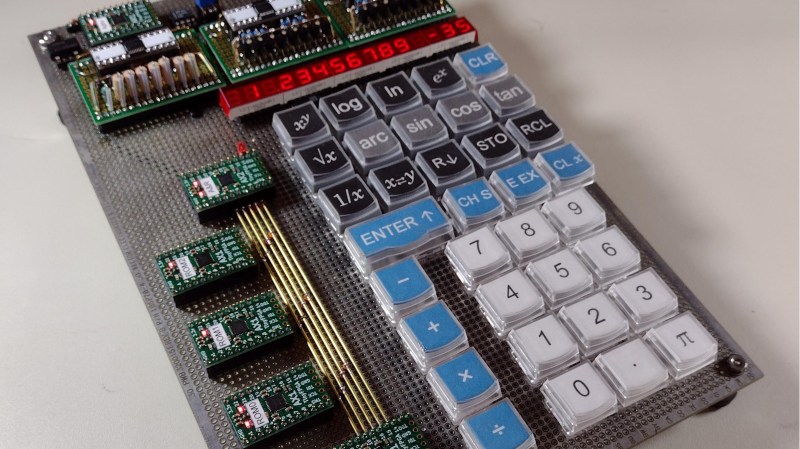

Once everything was working in the simulations, [Rob] set out to build a working model. TInyFPGA models were used, one for each custom chip. A few understandable departures were made from the original design. An 18650 lithium ion cell powers the board, kept topped off by a modern battery charging controller. The board is larger than the original, and yes, he’s using the Hackaday-obligatory 555 chip in the power-on circuit. In this short demonstration video, you can see the final prototype being put through its paces side by side with an original HP-35, working through examples from the owner’s manual.

This is an incredibly researched and thoroughly documented project. [Rob] has made the design open source and is sharing it on the project’s GitLab repository. [Rob]’s slides for Remoticon are not only a great overview of the project, but have some good references included. Its clear he has a real passion for these old calculators and has done a fantastic job exploring the HP-35. But even after three years, there’s more to come. He’s thinking about making a PCB version, and a discrete implementation using individual logic gates may be in the works.

We wrote about the history of the HP-35 before. And if you like hacking into these old calculators, check out our writeup of a similar dive into the Sinclair scientific calculator.

Post a Comment