The Seductive Pull Of An Obsolete Home Movie Format

It’s dangerous for a hardware hacker to go into a second-hand store. I was looking for a bed frame for my new apartment, but of course I spent an age browsing all the other rubbish treasures on offer. I have a rough rule of thumb: if it’s not under a tenner and fits in one hand, then it has to be exceptional for me to buy it, so I passed up on a nice Grundig reel-to-reel from the 1960s and instead came away with a folding Palm Pilot keyboard and a Fuji 8mm home movie camera after I’d arranged delivery for the bed. On those two I’d spent little more than a fiver, so I’m good. The keyboard is a serial device that’s a project for a rainy day, but the camera is something else. I’ve been keeping an eye out for one to use for a Raspberry Pi camera conversion, and this one seemed ideal. But once I examined it more closely, I was drawn into an unexpected train of research that shed some light on what must of been real objects of desire for my parents generation.

A Thrift Store Find Opens A Whole New Field

The Fuji P300 from 1972 is typical among consumer movie cameras of the day. It takes the form of a film magazine with a zoom lens assembly on its front, a reflex viewfinder on its side, and a handle with a shutter trigger button on it protruding vertically below the magazine and also housing the batteries.

Surprisingly it still has a mercury cell that would have powered its light meter; a minor annoyance to dispose of this correctly. Sometimes these devices had clockwork motors, but this one has an electric motor. It also has a light sensor that is coupled to some kind of electromechanical aperture. It would have been an expensive camera when it was new, probably as much of a purchase as an SLR or a decent mirrorless camera here in 2021.

The surprise came when I opened it up, for it looked like no other 8mm camera I had seen. I’m familiar wit the two reels of a Standard 8 or the boxy cassette of Super 8, but this one used something different. That film magazine is made to fit a compact twin-reel cartridge whose film fits in a metal film gate. This is a Single 8 camera, Fuji’s entry in the all-in-one 8 mm film market, and a format I never knew existed. To explain my unexpected discovery it was necessary to delve into the world of home movie formats in the decade before videotape arrived and drove them out.

The Home Movie Days Had Their Format Wars Too

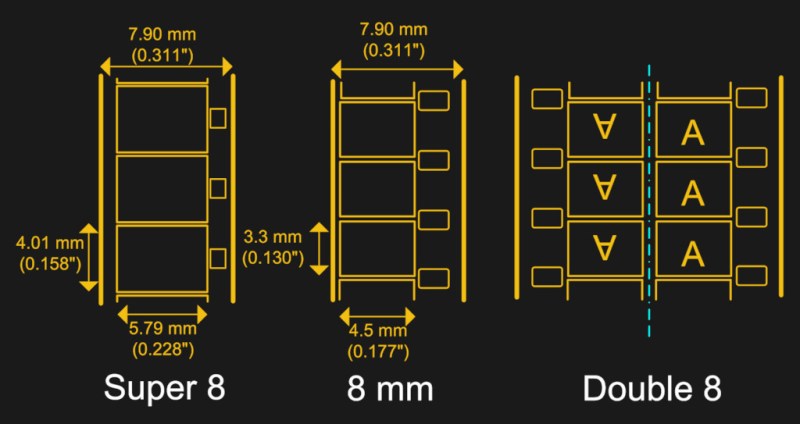

8 mm film dates from the early 1930s, when Kodak released the format as a cheaper alternative to 16 mm for the home movie market. The original 8 mm film, now known as Standard 8, is simply 16 mm film stock with twice the number of sprocket holes, which could be exposed on both edges by running it through the camera in both directions. The film strip would be cut in half and spliced together during development, resulting in a longer film strip with sprocket holes on only one side but with a short overexposed white section in the middle at the join depending on how successfully the user had kept the light at bay while swapping over the film reels. Starting in the 1960s, some manufacturers offered sound recording on a magnetic strip added between the sprocket holes and the edge of the film.

The shortcomings of Standard 8 with its inconvenient film swap-over, oversized sprocket holes, and unsatisfactory sound capabilities, led manufacturers to seek improved versions. Kodak’s Super 8 of 1965 had a larger picture area with smaller sprocket holes and sound capability designed in from the start, and came in a compact cartridge containing both reels one stacked above the other with no rewind facility. My camera’s Single 8 from the same year uses the same film format but on a thinner stock, and with separate reels. Arguments raged at the time over the relative merits of Super 8’s plastic film pressure plate over Single 8’s metal part, but reading around the subject, the consensus seems to be that both versions had a better picture quality that Standard 8.

It might be a surprise to some readers who are several decades on from their move to digital, that while Single 8 went out of production around a decade ago, both Standard 8 and Super 8 are still available — and have a significant enthusiast filmmaker following. Aside from the millions of simple home movie cameras like my Fuji, there were much higher quality professional-grade units, and these still command high prices. It’s attractive to pick up a Super 8 home movie camera and give it a go, but with film cartridges selling for around £40 (about $53) and offering only a few minutes of footage it’s hardly an inexpensive hobby.

A Teardown On A Device With Loads Of Tiny Screws, What Could Possibly Go Wrong!

This is the first time I’ve had a move camera on my desk, so it’s an ideal moment to dismantle it and take a look at its inner workings. And immediately I picked up the screwdriver it became evident that here is a very well designed and well built device indeed. Everything comes apart with very well-placed screws, and all screws are both easy to get to and turn as though they were last touched yesterday instead of five decades ago. Starting in the film magazine there’s a removable cover under the film cartridge below which can be found a gear train for the film advance, and a mechanism involving a PCB wiper switch for the film usage indicator. The motor drive is mounted in the handle alongside the batteries, with the same gear train driving both shutter and advance. For a Pi conversion there’s plenty of space for the Pi camera, but sadly the film pressure plate will need moving.

Turning my attention to the front, there is an aluminium cover that’s retained by two screws and the zoom ring on the lens. Some careful extraction of tiny grub screws deals with the lens rings, and the cover comes off to reveal the inner workings. The lens assembly has a mount casting that incorporates a prism and mirror for the viewfinder light path. This comes before the shutter, so it will be easy to retain in any digital conversion.

Below the prism is the aperture mechanism, as I suspected a tapered opening mounted on a moving-col meter movement. The shutter itself is visible below the aperture mechanism, but I didn’t expose it, there should be a pair of rotating discs with openings in them. The surprise comes in how little in the way of electronics it contains: aside from the light sensor and moving coil, that’s it. This is a triumph of electromechanical engineering miniaturised into a handheld device, and as ready to shoot now as it was when first unpacked back in the early 1970s.

So do I have any guilt in tearing apart an 8 mm camera for a Pi conversion? If it were a rare or high performance camera then perhaps to do so would be a minor crime, but for a plentiful and mass-produced consumer grade item, and particularly one whose film hasn’t been made for years, there’s little chance of it being anything but a paperweight otherwise.

So with this one I’ll need to stop the shutter in its open position and remove enough of the film gate and pressure plate assembly to fit one of the smaller Pi cameras with its lens removed. There’s plenty of space for a modern battery in the handle, and I’m considering whether I can 3D print a facsimile of a Single 8 cartridge to house both Pi and sensor, thus minimising the dismantling required. These lenses give the same vintage home movie quality to digital images as they did to the 8 mm film when they were new, so I hope any videos I make will be suitably distinctive.

Post a Comment