Linux Fu: Superpowers for Mere Mortals

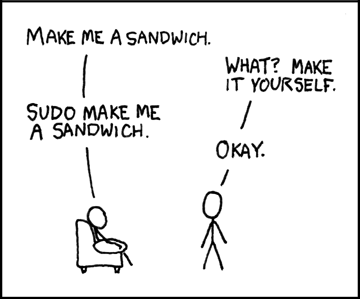

You can hardly mention the sudo command without recalling the hilarious XKCD strip about making sandwiches. It does seem like sudo is the magic power to make a Linux system do what you want. The only problem is that those superpowers are not something to be taken lightly.

sudo can handle that use case very easily.

Why?

As a simple example, suppose you like to shut your computer down at the end of the day. You run the shutdown command from the terminal but it doesn’t work because you aren’t root. You then have to do it again with sudo and if you haven’t logged in lately, provide your password. Ugh.

In my case, I got to thinking about this when I needed to manipulate the dbus service in a startup script. I wanted the script to manipulate just that service as a normal user and not prompt for a password, especially since some users don’t have sudo powers anyway. Either way, you would like a way to let normal users run very specific commands without additional permission.

A Simple But Bad Way

Your first thought might be to wrap the code in a shell script owned by root and set the suid bit so that when you execute it, the script elevates to having root access. That will work, but it seems like a potential security problem. After all, a script could do anything. Are you sure there is no way for a user to force it to do something else? Are you really sure?

Granted, you always have to think about this. If you, say, allowed someone to run emacs as root, that person could then open a shell and have full access to the system even if they didn’t otherwise have root access. That’s not good. But it is usually easier to reason about programs that have specific functions instead of a general-purpose shell script.

Configuration

That’s where

That’s where sudo comes in. There’s really only one place to set up sudo, although most modern distributions have that one place read files from a second place that you can also use. The primary place is /etc/sudoers and, as you would guess, you need to be root to change that file. In fact, you shouldn’t open it with a regular editor at all. Use visudo which verifies you aren’t going to lock yourself out of root access by messing up this file. That would be very bad on systems where there is no way to log in directly as root.

When you use visudo, an editor launches. These days that’s often nano by default, although vi is the historic choice as you can see by the name. If you prefer something else, the tool will pick up your VISUAL or EDITOR environment variable. Well… sort of.

The authors of visudo and sudo were paranoid and rightfully so. There are options to remove all environment variables before running a command or to preserve just selected ones. So most of the time if you try to set one of these environment variables it is wiped out by sudo. To fix that, you’ll have to survive with whatever editor you get by default one time. You can preserve the environment variables and provide a list of accepted editors by putting this near the top of the file:

Defaults env_reset Defaults env_keep=VISUAL Defaults env_keep=EDITOR Defaults editor=/usr/bin/nano:/usr/bin/emacs:/usr/bin/vi

Keep in mind that your DISPLAY variable won’t go through either, so don’t expect a GUI editor to work without some further configuration changes.

If visudo doesn’t like your changes because of a syntax error it will ask you what to do. Press ? to see your options. You can tell it save anyway, but I don’t recommend that.

Now What?

There are many arcane syntax commands you can put in

There are many arcane syntax commands you can put in sudoers to get different effects. In this case, we want to run a command like shutdown or service without a password for a specific user. Say the user is jolly_wrencher:

jolly_wrencher ALL= NOPASSWD: /usr/sbin/shutdown

This tells sudo that the user on all machines can run the command with no password. If the command takes parameters, the user is free to supply them. However, you can also provide parameters that must match or use a quoted space to imply no arguments allowed.

In the case of something that is disallowed, sudo may still let you run the command if you provide the password and you were otherwise allowed to run it. Otherwise, no dice.

For example, with the dbus example, I used two lines:

jolly_wrencher ALL= NOPASSWD: /usr/sbin/service dbus status jolly_wrencher ALL= NOPASSWD: /usr/sbin/service dbus --full-restart

Easier Maintenance

Many distributions will now have a final line in the sudoers file that looks like this:

#includedir /etc/sudoers.d

This will scan the directory named for files (unless they have ~ or . characters in the name) and process them, too. So in my case, I have the two lines about dbus in a file /etc/sudoers.d/dbus-service. You still should use visudo to edit. In recent versions, you just pass the name of the file you want to edit. Old versions needed a -f option. After editing, the system checks the entire sudoers file for errors, so it is safer than editing the files directly.

There’s quite a bit more you can do with sudoand sudoers. However, you should resist the urge to do too much. It is easy to make assumptions about security that get you in trouble. However, there are always cases where you need this kind of power and, as usual, Linux doesn’t disappoint.

Post a Comment