Flat-Pack Pasta: Like Ikea Furniture Without the Weird Wrench

When it comes to food packaging, there’s no bigger scam than potato chip bags, right? People complain about the air (nitrogen, actually) inside, but it’s there for a reason — nitrogen pushes out oxygen, so the chips live in a state of factory-fresh dormancy until you rip open the bag and release the gas. If you want flat-pack chips, there’s always those uniformly-shaped potato slurry wafers that come in a can. But even those usually manage to have a few broken ones.

On the other hand, no one complains about the extra space in their box of fusilli — that would be silly. But seriously, successfully shipping fragile foods requires either flat packing or a lot of extra space, especially if that food comes in a myriad of fun 3D shapes like pasta does. Everybody knows that 3D pasta is superior to flat pasta because it holds sauces so much better. The pasta must be kept intact!

The great thing about pasta as a food is that it’s simple to make, and it’s more nutritious than potato chips. Because of these factors, pasta is often served in extreme situations to large groups of people, like soldiers and the involuntarily displaced. But storing large quantities of shapely pasta takes up quite a bit of space. And because of all that necessary air, much of the packaging goes to waste.

So what if you could keep your plethora of pasta in, say, a filing cabinet? A research team led by the Morphing Matter Lab at Carnegie Mellon University have created a way to make flat-pack pasta that springs to life after a few minutes in boiling water.

This probably goes without saying, but they were inspired by IKEA’s packaging MO and sought to apply that flat-pack principle to food. The team has spent the last few years experimenting with 2D films of cellulose, protein, and starch to make them morph into 3D shapes as they absorb water. However, their method required additives, which likely wouldn’t fly with consumers or pasta manufacturers. So they came up with a way to do it by stamping the pasta, which they call “groove-based transient morphing“. Sounds to us like the one thing that can supplant lo-fi/hip-hop beats to study/relax to.

Why Didn’t We Think of This?

We love the simple utility of this so much. It’s like kerf-bending wood, or running a scissor blade along grosgrain ribbon in order to curl it. It would be dead simple to recreate this experiment at home with 3D-printed stamps, as long as you used food-safe mold release like the researchers did.

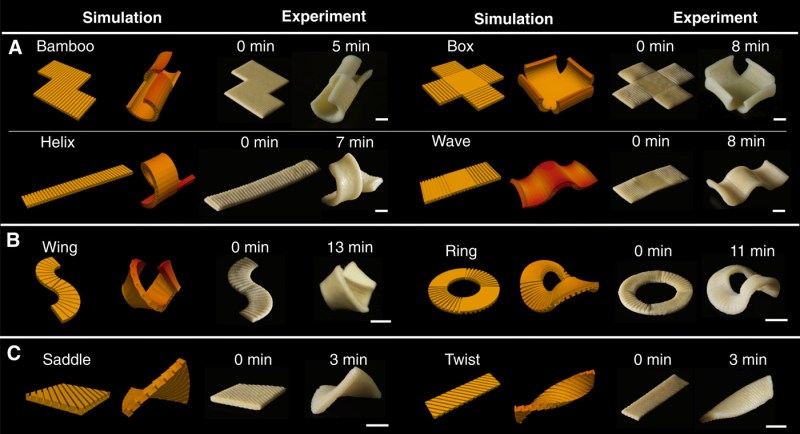

In order to find a suitable morphing mechanism for pasta, the team turned to PDMS, a silicone that is widely used to study kinetic behaviors. They experimented with groove types, weighing cuboid-shaped square wave grooves against frustrum-shaped Kit Kat side-view grooves, and found that the frustrum-shaped grooves maximized the curvature of the bent PDMS. With the morphing mechanism sorted, the researchers traded their lab coats for aprons and got to work applying it to dough.

The team starts with simple sheets of pasta made the traditional Italian way, with nothing but semolina flour and water. The dough is rolled out flat and cut down into shapes as normal, although most of them are new and exciting. Finally, they stamp the dough with pieces of plastic they designed and 3D printed, using a food-safe mold release in between. They started out with hand stamping, and as you can see in the video below, they ended up using a four-axis gantry for more precise impressions. Then it’s business as usual: boil the pasta for 7-12 minutes depending on shape and thickness, and watch the morphing take place. It takes longer to soften where the grooves are, and they don’t expand as much as the smooth parts. One team member took a matchbox of flat-pack pasta on a hike and cooked it over a fire to prove its utility.

Juicier Than Square Watermelons

A bit of quick research reveals that MIT had the same idea a few years ago. So why hasn’t the idea taken off? Obviously, someone needs to make a Kickstarter and stand up a flat-pack pasta company.

The question is, how much more would this pasta cost to consumers? It wouldn’t have to be much, right? We were neither business nor industrial design majors, but how much could the overhead be on a company like that? Surely flat-pack pasta is an idea that wouldn’t go limp, like square watermelons.

Growing watermelons inside of cube molds was supposed to be a refrigerator space-saving initiative that would make stacking a breeze. In reality, they cost $100-$200 each because they don’t all grow with perfectly vertical stripes or fill the mold. And because each must be picked before they’re ripe, they’re basically inedible and mostly used for decoration.

We imagine that if flat-pack pasta became a thing, it wouldn’t be perfect — there would probably still be a few broken ones just like those flat-pack potato wafers. But who cares? They’ll still hold sauce.

Post a Comment