Weren’t We supposed To Live In Plastic Houses In The Future?

Futurism is dead. At least, the wildly optimistic technology-based futurism of the middle years of the 20th century has been replaced in our version of their future by a much more pessimistic model of environmental challenges and economic woes. No longer will our flying cars take us from our space-age wonder-homes to the monorail which will whisk us through sparkling-clean cities to our robotised workplaces, instead while we may have a global computer network and voice controlled assistants we still live in much the same outdated style as we did decades ago. Our houses are made from wood and bricks by blokes with shovels rather than prefabricated by robots and delivered in minutes, and our furniture would be as familiar to a person from the 1950s as it is for us.

A Plastic Future That Never Quite Happened

There was a time when the future of housing looked remarkably different. Just as today we are busily experimenting with new materials and techniques in the type of stories we feature on Hackaday, in the 1950s there was a fascinating new material for engineers and architects to work with in the form of plastics. The Second World War had spawned a huge industry that needed to be repurposed for peacetime production, so almost everything was considered for the plastic treatment, including houses. It seemed a natural progression that our 21st century houses would be space-age pods rather than the pitched-roof houses inherited from the previous century, so what better way could there be to make them than using the new wonder material? A variety of plastic house designs emerged during that period which remain icons to this day, but here we are five or six decades later and we still don’t live in them. To find out why, it’s worth a look at some of them, partly as a fascinating glimpse of what might have been, but mostly to examine them with the benefit of hindsight.

The most famous of the plastic house designs is the Futuro, designed in the late 1960s by the Finnish architect Matti Suuronen originally as a skiing lodge but later commercialised in modest numbers across the globe. It’s a sectional fibreglass reinforced plastic design that resembles a flying saucer, with oval windows around its circumference and a Learjet-style folding staircase for its entrance. It stands on a tubular frame that locates with four concrete pads, making it capable of being placed on almost any terrain. Internally it has several rooms and fitted furniture incorporated into its curved shape.

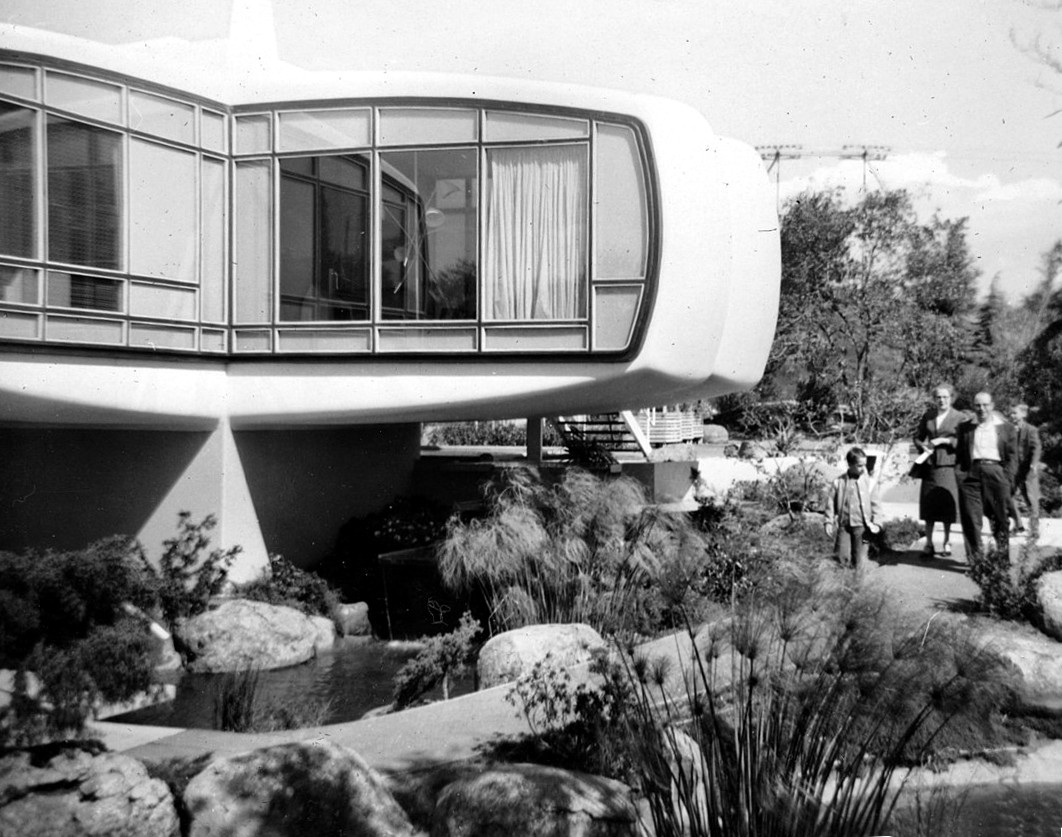

It wasn’t the only famous plastic house of the era even though it was the one most commercialised, aside from Suuronen’s smaller Venturo design there were also buildings such as Jean-Benjamin Maneval’s Bubble House and the Disney Corporation’s popular Disneyland attraction, the Monsanto House Of The Future which happened to be MIT-designed and was visited by many millions of people from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. These were both more practical designs than the Futuro, in which fibreglass modules would be assembled from central structures in a variety of configurations. The Disney house’s modules had steel frames cantilevered from a central concrete tower containing the building’s utilities, and was a serious attempt to model a house for a typical American family. All of its internal furniture and features were also made from plastic as a showcase of the new material, and though it was never inhabited there are period films showing park cast members acting the roles of residents. (As an aside, the central tower foundation is said to survive to this day at the park as a planter.)

So Where Did It All Go Wrong?

Given that the technology was proven by the serial production of the Futuro, ultimately by the longevity of the surviving houses, and by the resilience of the Disney house under the pressure of millions of visitors, it is evidently not a lack of practicality that caused them not to catch on. Maybe your tastes are different, but I for one would happily live in a clone of the Disney house if I were satisfied of its fire safety, and were someone to offer me the keys to a Futuro I’d have my bench installed within the day. But perhaps surprisingly given our popular view of the era as an explosion of the new, they struggled to gain acceptance when placed in real-world locations.

In fact though its influence on later decades was huge, the 1960s mod-wonderland showcased in popular myth like the Austin Powers movies was in reality restricted to a relatively few places and select age groups, and the appearance of a Futuro at the end of the street would have been too much for the more conservative residents whose tastes would have been formed decades earlier. Those few Futuros and their ilk which were built faced hostility from their neighbours, and were excluded by planning ordinances and home finance companies. The oil crisis of the early 1970s provided the death-knell by driving up the price of the raw materials, and by the 1980s that future was but a distant memory.

Turns Out You Can’t Order Everything from Amazon

Perhaps a further surprise comes in how relatively few of us today live in truly prefabricated homes (as opposed to site-built kit homes) even if they aren’t made from plastic. We have an immense demand for affordable housing in developed countries coupled with a building industry still using intensive techniques perfected in another century, and these conditions should be a perfect environment for prefabricated housing.

Manufactured prefabrication of housing units has a long history in many countries from Soviet apartment blocks through Western European high-rise buildings to Japanese and American modular homes. But they still meet resistance from local planning authorities, in building codes, and sometimes even from would-be customers themselves. In some respects this is driven by the interests of a construction industry that would face ruin were the need for its thousands of wet-trade workers to end, but in others it seems driven by a continuing obsession with making houses look as though they were made centuries ago. Perhaps if we are ever to solve our housing crises, we need once more to revive futurism. After all, our children might need it.

Header image: Futuro house, Nan Palmero (CC BY 2.0).

Post a Comment