The Wright Stuff: First Powered Flight on Mars Is a Success

When you stop to think about the history of flight, it really is amazing that the first successful flight the Wright brothers made on a North Carolina beach to Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon spanned a mere 66 years. That we were able to understand and apply the principles of aerodynamics well enough to advance from delicate wood and canvas structures to rockets powerful enough to escape from the gravity well that had trapped us for eons is a powerful testament to human ingenuity and the drive to explore.

Ingenuity has again won the day in the history of flight, this time literally as the namesake helicopter that tagged along on the Mars 2020 mission has successfully flown over the Red Planet. The flight lasted a mere 40 seconds, but proved that controlled, powered flight is possible on Mars, a planet with an atmosphere that’s as thin as the air is at 100,000 feet (30 km) above sea level on Earth. It’s an historic accomplishment, and the engineering behind it is worth a deeper look.

The Long Deployment

Ingenuity is what’s known as a “technology demonstrator,” which is essentially an ancillary mission that tags along with the main scientific payloads supporting the primary mission. In many ways, tech demonstrators are afterthoughts, forced to fit into odd nooks and crannies and to impact the primary science missions as little as possible. Still, Ingenuity was afforded a considerable slice of the resources offered by the Perseverance rover, and a large chunk of mission time — 30 sols, or Martian days — to complete everything it could.

While it seems like 30 sols would be plenty of time to deploy, test, and fly Ingenuity, it’s actually a pretty tight schedule — nothing is easy when you’re doing it on Mars, after all. With that in mind, NASA front-loaded Perseverance’s schedule with Ingenuity operations, planning to knock out everything that the Ingenuity team had planned before proceeding onto the main mission of exploring Jezero crater for signs of ancient life.

The first thing Perseverance had to do was deploy Ingenuity onto the Martian surface. We’ve seen footage of the deployment tests, which gave the impression that birthing the helicopter onto the surface would be the work of a few minutes at most. But again, nothing about exploring another planet is easy, and with only one chance to get the first flight on another planet right, the Ingenuity team took no chances and made the deployment a painstaking process that took more than three weeks to complete.

Job one was to jettison the debris shield that cocooned Ingenuity during its ride across space and onto the surface of Mars. Once cameras confirmed that the cover had dropped off cleanly and that the aircraft had suffered no visible damage, Perseverance drove a considerable distance to the designated drop-off area. The flight team was obviously very picky about the terrain in the flight zone, as rocks could cause a problem for the helicopter while landing autonomously.

Once a suitable area was located, the long process of deploying the stowed helicopter to the surface began. Ingenuity was shipped on its side, with two of its four landing gear folded up. The aircraft was released from its locks and swung down into a vertical position, partly under the force of gravity and partly with the help of a small motor. After locking into the vertical position, the two folded legs were released, springing down into position thanks to the shock-absorbing mechanisms attaching them to the hull of the aircraft.

Finally, when the team was sure that everything checked out and the drop zone was clear of obstructions, the command was sent to deploy Ingenuity to the surface. It dropped few inches and landed cleanly on the surface on April 6. This was a big moment for the flight team — Ingenuity was now on its own, untethered from the power and data connections to Perseverance. The tiny aircraft would now have to survive solely on the power generated by its small solar panel and stored in its batteries, and have to prove that it could keep itself warm enough during the harsh Martian nights.

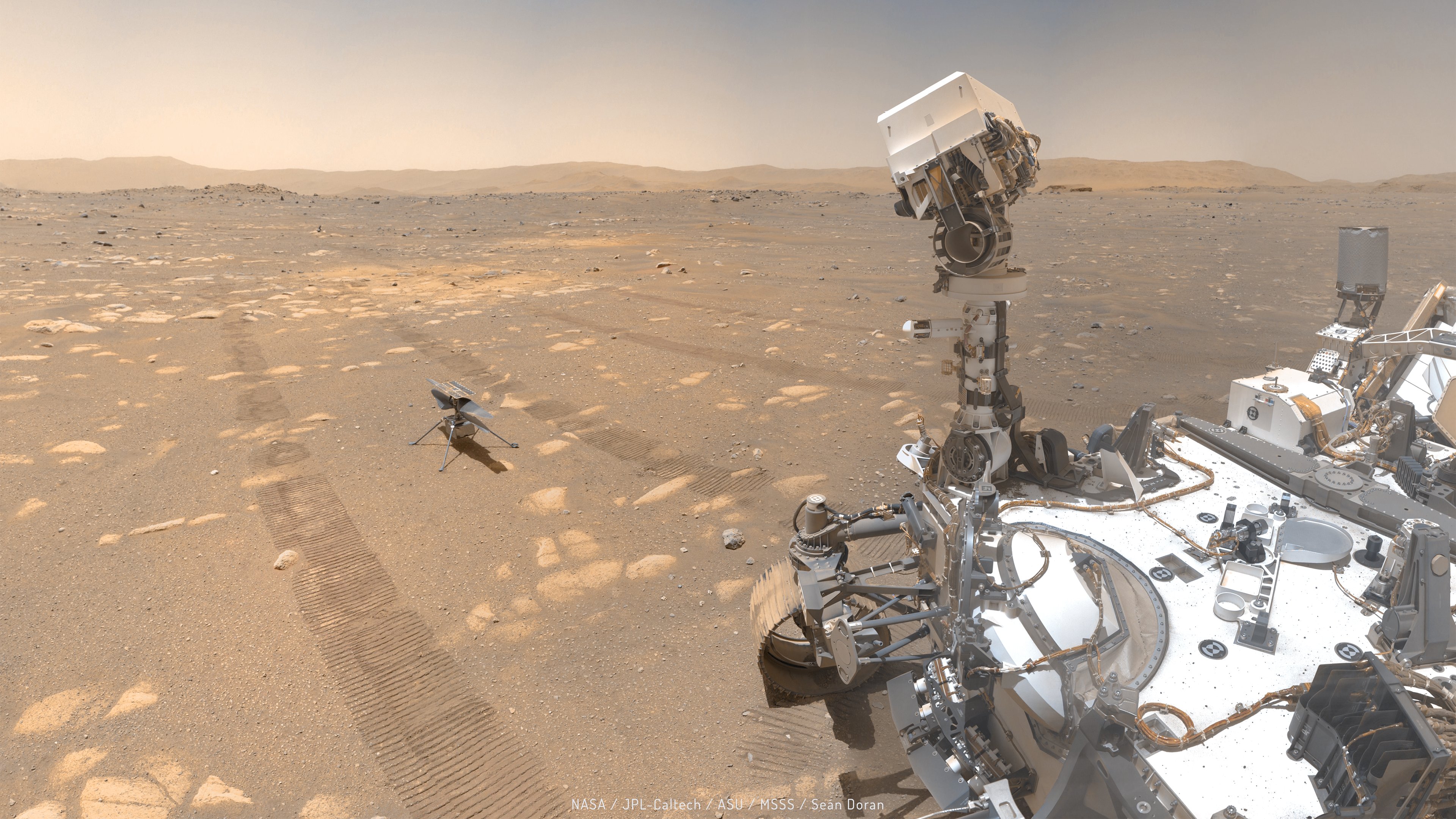

While the Ingenuity team was doing these checks, the rover moved about 4 meters away, exposing the helicopter’s solar panels to the sun for the first time. And like any tourist, Perseverance took a selfie with its former passenger in the background before heading off to its designated overwatch location, which is on a small rise about 60 meters from the drop-off location.

Since deployment, Ingenuity has been busy running system tests to make sure it’s ready to fly. The test results, including unlocking the rotor blades and doing a low-speed rotation test on April 8, were promising enough that NASA announced that the first flight would occur sometime on April 11, pending one final test — the full-speed rotor spin-up. While the rotors did manage to spin up to full speed on April 9, the flight software on the helicopter tripped a watchdog timer while trying to switch from pre-flight mode to flight mode. This caused a delay in the first flight attempt, at first by just a few days.

But as the new date for the first flight came and went, it was announced that a rewrite of the flight software would be necessary. Of course, this required extensive testing and subsequent upload of the new software to Ingenuity. While waiting for the bandwidth to accomplish these tasks, the flight team was able to complete the full-speed spin-up test, allowing them to schedule the first flight attempt for the early morning hours of April 19. The flight plan was very modest — take off, rise slowly to an altitude of 3 meters, hover in place for 30 seconds before yawing, and touch back down in the same place it took off from.

First Flight

For as exciting as the first flight of Ingenuity was, the coverage of it was somewhat anticlimactic, mainly due to the fact that the flight had already occurred, and all that was left was waiting for the data to pour in. So there was a fair amount of waiting around as the team stared at their screens. But eventually enough data came back to show that Ingenuity has spun up, ascended, hovered, descended, landed, and spun down without any incidents.

Things got more exciting when the plot of altimeter data came in, showing that Ingenuity had gotten up to just over three meters above the surface for a few seconds. But then the first images rolled in. A single black and white still from the down-looking navigation camera showed the shadow of Ingenuity cast onto the Martian surface, neatly framed by Perseverance’s wheel tracks. And shortly thereafter, images from the cameras on Perseverance came back, clearly showing the whole flight.

Now that the goal of proving that controlled flight on Mars is possible has been met, Ingenuity still has a host of experiments to conduct. MiMi Aung, project manager for Ingenuity, said that after the first flight, longer, more complex flights would be undertaken. There are hard limits to those flight profiles, of course — Ingenuity won’t be buzzing over to where Perseverance is parked, for example. But the helicopter will fly higher and farther than its first flight, testing the limits of the aircraft.

And while it wasn’t explicitly stated, it was certainly implied that at some point, Ingenuity may just end up crashing due to the flight operation team exceeding the limits of what the aircraft can handle. That’s fitting, in a way — Ingenuity was always on a one-way trip into the history of flight, and finding out what the limits of operating in the Martian atmosphere are is probably as good an end as any for the first Martian aircraft to meet.

Still, it might be nice if Ingenuity finishes its final flight with a nice touchdown, ready to be picked up by some future explorer and placed in some future Martian air and space museum, like the Wright Flyer is displayed today. If that happens, the circle will be complete, because tucked away aboard Ingenuity, wrapped around a cable under the solar panel, is a tiny swatch of muslin from the wing of the Flyer.

Post a Comment