Teardown: Linkimals Musical Moose

Like so many consumer products these days, baby toys seem to get progressively more complex with each passing year. Despite the fact that the average toddler will more often than not be completely engrossed by a simple cardboard box, toy companies are apparently hell-bent on producing battery powered contraptions that need to be licensed with the FCC.

As a perfect example, we have Fisher-Price’s Linkimals. These friendly creatures can operate independently by singing songs and flashing their integrated RGB LEDs in response to button presses, but get a few of them in the room together, and their 2.4 GHz radios kick in to create an impromptu mesh network of fun.

Once connected to each other, the digital critters synchronize their LEDs and sing in unison. Will your two year old pay attention long enough to notice? I know mine certainly wouldn’t. But it does make for a compelling commercial, and when you’re selling kid’s toys, that’s really the most important thing.

On the suggestion of one of our beloved readers, I picked up a second-hand Linkimals Musical Moose to take a closer look at how this cuddly pal operates. Though in hindsight, I didn’t really need to; a quick browse on Amazon shows that despite their high-tech internals, these little fellows are surprisingly cheap. In fact, I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that given its current retail price of just under $10 USD, I actually paid more for my used moose.

But you didn’t come here to read about my fiscal irresponsibility, you want to see an anthropomorphic woodland creature get dissected. So let’s pull this smug Moose apart and see what’s inside.

Infant Engineering

Being that this it the first gadget intended for actual infants that we’ve taken a look at here in this continuing series of teardowns, it’s worth noting the little details that come with the territory. There isn’t a sharp corner on the moose, and the few visible screws have been set deeply enough into the plastic that even the most inquisitive youngster couldn’t get them out.

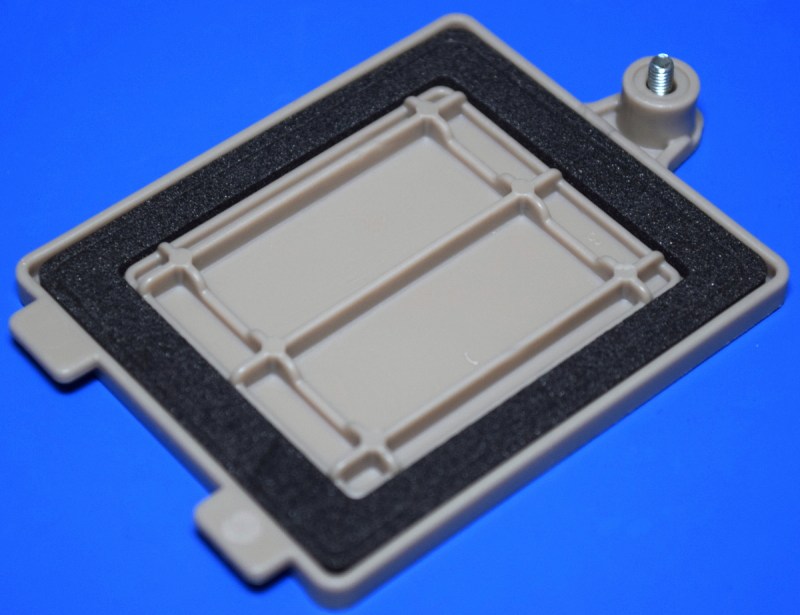

It’s also interesting to see that the battery compartment has been made impervious to liquids by way of a generous gasket around the door and sealant at the top where the terminals pop through the plastic. Remember, this toy isn’t intended to go anywhere near the water. So was this an effort to keep saliva out of the internal workings, or to make sure the crusty goodness of a popped alkaline cell didn’t find its way into junior’s mouth? When dealing with users of this age, perhaps it’s a little bit of both.

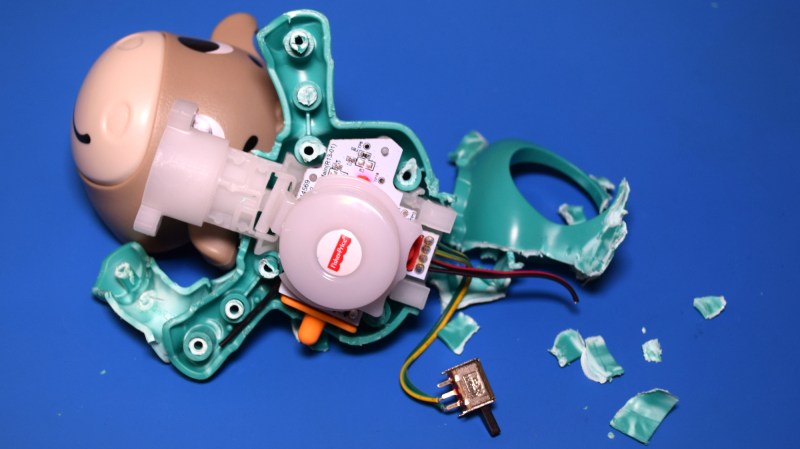

Unfortunately, it turns out this construction method isn’t exactly conducive to non-destructive teardowns. While the feet and head of the Musical Moose come off with no problem, the body itself, where all the electronic goodies live, appears to be permanently sealed. Try as I might with all manner of prying implements, I simply couldn’t get this thing to open up. Ultimately I had to start cutting away at the plastic, which eventually uncovered the eight pegs holding the two halves of the body together. I’m not sure if they were glued or ultrasonically welded, but the end result is the same: a very traumatic scene for any little ones who might wander over to the bench.

A One Two Chip Solution

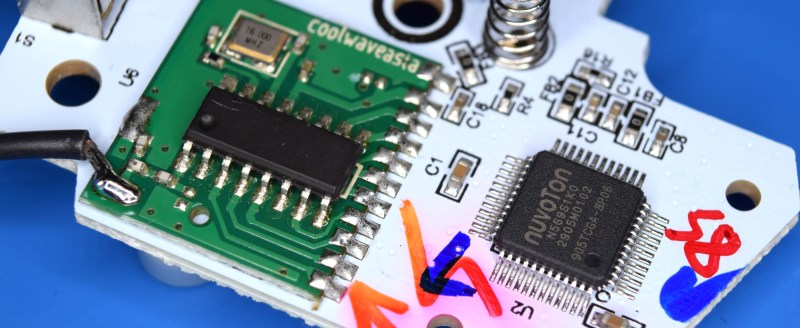

Given the incredibly low price of this toy I expected to see at least a few black epoxy blobs on the inside, but the reality ended up being quite a bit more interesting. Outside of an RGB LED, a button, and a handful of passives, there are just two components on the Musical Moose PCB. One of them, while being completely devoid of any markings, is clearly the radio. The other is a fascinating all-in-one solution from Nuvoton specifically designed for talking gadgets like this.

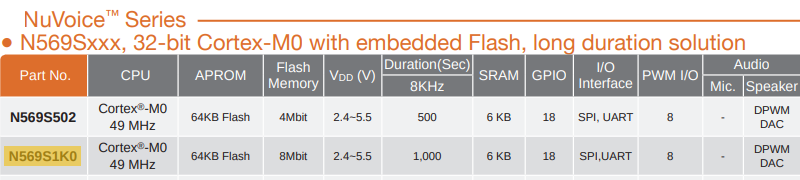

The Nuvoton N569S1K0 is an ARM Cortex-M0 32-bit microcontroller running at 49 MHz with 6 kB RAM and 64 kB ROM. As part of the company’s NuVoice series of chips, it also features 1 MB of internal storage for audio data. According to the spec sheet, that allows the single chip to hold nearly seventeen minutes worth of voice clips. Not at a particularly high quality, mind you, but more than good enough for a talking toy.

Clearly the soldered on module with the antenna lead is the radio, but other than the name Coolwaveasia on the silkscreen, there’s nothing to identify it. Searching the name we can see it’s a product of Coolwave Communications, and browsing through their site even shows some very similar looking modules, but none of them appear to have a publicly available datasheet.

Radio Research

Soldered on radio modules are a common sight when taking apart cheap wireless gadgets, as it saves the designers from having to figure out the RF side of things. But without a datasheet, it’s difficult to say exactly what we’re looking at here. Is this chip just a simple radio, or is it a microcontroller of its own? After all, that’s a lot of pins just to pass a few bytes of data back and forth. Unfortunately, without more information to go by, this is where the trail often ends up going cold.

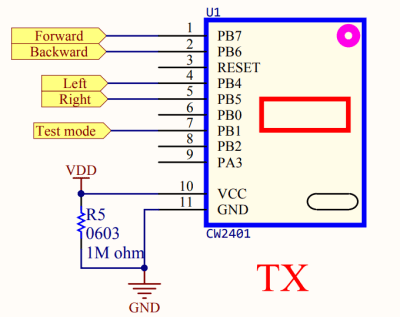

But not this time. After a bit of searching I found an FCC entry for the Jurassic World “Raptor Attack Jeep” that appeared to use the same radio module. That alone wouldn’t have been too helpful, but unlike the vast majority of FCC database entries for commercial products, this one actually had its circuit diagrams available. What’s more, under “Technical Description”, it included the module’s datasheet from Coolwave Communications.

With this information in hand, we can see that communication with the radio module is very simple. It’s not using I2C, SPI, or even UART. Instead each pin appears to correspond to its own channel, and transmitting on it is as easy as grounding it out. Indeed, the Jeep’s circuit diagram shows that the Forward/Backward and Left/Right lines are connected directly to push buttons. The module’s documentation goes on to explain that the pins can be configured as input or output, which presumably makes reception as straightforward as waiting for the pin to go low.

Talking to the Animals

So where does that leave us? Well we’ve got a pretty good idea of how the Nuvoton MCU talks to the radio module, and one very mangled Musical Moose. Rather than toss the parts in the trash, I decided to wire in a header between the two chips so I could plug in a logic analyzer. With a little hot glue holding it together, the Moose Sniffer was born.

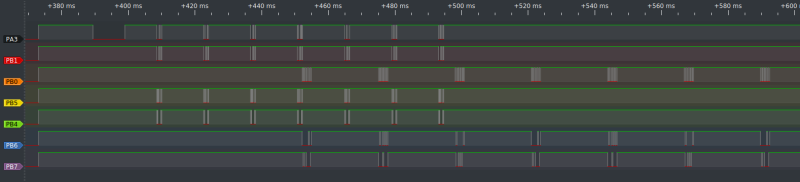

At the moment I don’t have any other Linkimals, so I can only look at what the massacred moose is sending out. It doesn’t appear to be any traditional communications protocol, which given how the Jurrasic World toy used the radio module, isn’t a great surprise. Three of the channels send out a few bits in a clearly repeating pattern, perhaps as some sort of heartbeat or discovery signal for the other critters to key in on. Pressing the button to make the moose sing fires a few extra bits off on these same channels.

Four of the channels initially see some chatter right after power up, but then quiet down and don’t show any more activity. Presumably these are the receive channels which would light up when another animal is in the vicinity, but I won’t know for sure until I get my hands on a few more Linkimals. Given how cheap they are that shouldn’t be a problem, and now that I have a dedicated sniffer, I won’t even have to take the others apart. Which is good, since I don’t think my daughter would forgive me if any more of these fellows met the same fate as the Musical Moose.

High Tech, Low Cost

I plan on exploring the communication between these toys in the near future, and hopefully will be able to revisit the subject with another article. But in the meantime, the biggest takeaway from the teardown of the Linkimals Musical Moose is that you don’t have to break the bank to pack some legitimately impressive technology in your product.

Fisher-Price is selling these things for a song, and each one includes 2.4 GHz mesh networking and a powerful 32-bit microcontroller with onboard audio capabilities. Sure you can get an ESP32 for five bucks, but this is a fully developed and marketed product with all the expenses that entails. Yet they’re still making a profit at $10. Toys have historically been a pretty good indicator of what contemporary low budget hardware has looked like, and it makes you wonder what kind of technology will be backed into a child’s plaything in another decade. One thing’s for sure: I can’t wait to take one of them apart.

Post a Comment