Wet Country Wireless; How The British Weather Killed A Billion Pound Tech Company

A dingy and cold early February in a small British town during a pandemic lockdown is not the nicest time and place to take your exercise, but for me it has revived a forgotten memory and an interesting tale of a technology that promised a lot but delivered little. Walking through an early-1990s housing development that sprawled across the side of a hill, I noticed a couple of houses with odd antennas. Alongside the usual UHF Yagis for TV reception were small encapsulated microwave arrays about the size of a biscuit tin. Any unusual antenna piques my interest but in this case, though they are certainly unusual, I knew immediately what they were. What’s more, a much younger me really wanted one, and only didn’t sign up because their service wasn’t available where I lived.

All The Promise…

Ionica was a product of Cambridge University’s enterprise incubator, formed at the start of the 1990s with the aim of being the first to provide an effective alternative to the monopolistic British Telecom in the local loop. Which is to say that in the UK at the time the only way to get a home telephone line was to go through BT because they owned all the telephone wires, and it was Ionica’s plan to change all that by supplying home telephone services via microwave links.

Their offering would be cheaper than BT’s at the socket because no cable infrastructure would be required, and they would aim to beat the monopoly on call costs too. For a few years in the mid 1990s they were the darling of the UK tech investment world, with a cutting edge prestige office building just outside Cambridge, and TV adverts to garner interest in their product. The service launched in a few British towns and cities, and then almost overnight they found themselves in financial trouble and were gone. After their demise at the end of 1998 the service was continued for a short while, but by the end of the decade it was all over. Just what exactly happened?

The technology behind Ionica’s service could probably be replicated for a few dollars worth of WiFi modules in 2021, but at the time it lay at the bleeding edge of what was possible near the consumer end of the market. A tower was erected with a base station for each community to be served, and if the customer’s premises were on a line-of-sight from it they could have that biscuit-tin antenna installed.

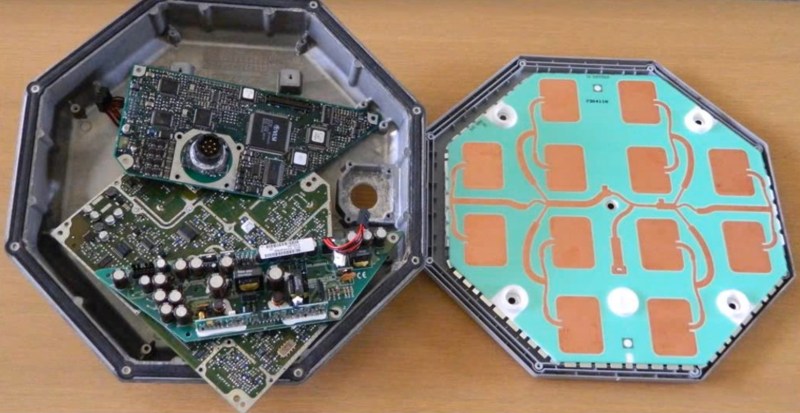

The fixed line-of-sight link operated at 3.5 GHz, and used custom hardware made for Ionica by Nortel Networks. A teardown on a surviving unit from 2015 which we’ve placed below the break was put up on YouTube in 2015, and it reveals a phased array of patch antennas as well as the RF and control boards. The overwhelming impression is that this would have been an extremely expensive device to manufacture in the mid 1990s, as many of its exotic RF functions would now be integrated into newer silicon and probably performed using SDR technology.

… But Not Quite The Delivery

To be on a housing estate like the one I saw the antenna on in the winter of 1996 or so would have been to see Ionica technicians doing site surveys and making installations. There was genuine demand for the service at the time, as BT’s monopoly meant a high line rental and call charges, and the promise of not one but two phone sockets allowed the possibility of using the phone and the Internet alongside each other. Heavy stuff a quarter century ago, and I wanted one.

Perhaps it’s just as well that I didn’t have the chance, because I would surely have lost money (It wasn’t the only time that decade I failed to see the inevitable!). Shortly after the hype surrounding the service’s availability there surfaced stories of it dropping out during wet weather. We were assured that they were working on a solution, but worse was yet to come.

As spring turned into summer in about 1997, some customers struggled to receive any service at all, at fault was the verdant British tree foliage. It seems that site surveys performed in winter failed to take account of summer leaves obstructing the line-of-sight to the base station, and this seasonal service only added to the company’s woes.

With hindsight, Ionica’s product was one in some ways before its time, yet in others, one whose time had nearly passed. The expensive hardware and limited base station range would now be solved using much cheaper SDR chipsets and many more base stations, so in this decade the roll-out could have been performed much more easily and reliably. But the product itself now seems ludicrously dated, because who now needs a pair of analogue phone lines? ADSL connections arrived in the UK around 2000, so very shortly after the company’s demise they would have been stuck with a product that couldn’t deliver customer expectations. Could they have used the same hardware to deliver an always-on connection? Perhaps, but it never appeared in their published plans, and it’s unlikely that it would have had enough bandwidth to compete with ADSL.

It’s now over two decades since Ionica’s demise, and while cable TV fibre and local loop unbundling to put ISP racks in telephone exchanges have changed the telecom landscape significantly, there remains for most people a last mile connection owned by BT. Wired analogue phones are now a legacy item that increasing numbers of people only have because it comes with their broadband line, and even mobile calling is inexorably being usurped by online services.

Perhaps only now with the arrival of 5G mobile phones we’ll see that lingering BT last-mile monopoly broken. Meanwhile aside from a few weathered antennas in suburbia little remains of the company; its base station hardware turns up on eBay and is sought-after by radio amateurs and its prestige headquarters building by the A14 in Cambridge is now home for several occupants of the city’s wildly successful technology park. Brits spend a lot of their time battling the rain, but it’s not often that it brings down a billion pound company.

Post a Comment