Retrotechtacular: CT2, When Receiving Mobile Phone Calls Wasn’t A Priority

Over the years we’ve brought you many examples in this series showing you technologies that were once mighty. The most entertaining though are the technological dead ends, ideas which once seemed as though they might be the Next Big Thing, but with hindsight are so impractical or downright useless as to elicit amazement that they ever saw the light of day.

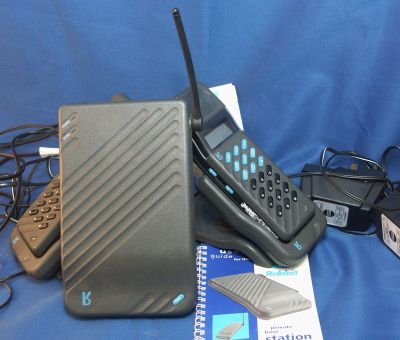

Today’s subject is just such a technology, and it was a serious product with the backing of some of the largest technology companies in multiple countries from the late 1980s into the early ’90s. CT2 was one of the first all-digital mobile phone networks available to the public, so why has it disappeared without trace?

The Future’s Cordless, Not Cellular!

The idea was simple: to bridge the gap between a domestic cordless telephone and a mobile phone, by supplying a handset that could not only work with your base station at home, but also make calls from commercial base stations when you were out and about. Instead of a bulky brick of an analogue cellular phone you’d sport a svelte and stylish handset, and place important calls while striding across a railway station concourse on your way to high-powered business meetings. It was intended as a replacement for the pretty awful analogue cordless phones of the day, and here in the UK it was an idea tried out by multiple companies and the IEE Review foresaw a bright future for it.

The technology was for its time quite revolutionary in a consumer product, ADPCM-digitised 32 kbit digital data streams multiplexed on carriers in the range of 864 to 868 MHz. The handsets were not powerful at only 10 mW output, which was probably the main reason for their claimed 100 m range from a base station. Because they were a fancy take on a cordless home phone rather than a fully-fledged mobile phone their users had to authenticate with each new base station by typing in a PIN, this shortcoming meant that they could only receive calls through the landline on their owner’s home base station. There was no automatic handover between adjacent base stations, so it was not a cellular system.

An Exercise In How Long Defunct Signage Can Stick Around

Given that it received national publicity, why did each company in turn try their luck in the market only to fail? In the first instance the handsets themselves were significantly expensive, in the region of £200 (over $300 in 1990 terms), which put their cost well out of reach of those non-mobile-owning customers who might be tempted by a cheaper alternative. Then on top of that there was a monthly subscription and call charges, further increasing the costs.

The real killer though was that a base-station-dependent network faced an impossible task in providing enough coverage to ensure that its users had a chance of being somewhere they could use it. They could be found in public places such as rail and bus stations, motorway service stations, and shopping centres, but even a roll-out to small convenience stores could not provide the required penetration. The best-known of the networks, Rabbit, was at its peak while I was a student, and though it was the time when a few students were already sporting mobile phones, in conversation with friends there’s not one of us who could remember knowing anyone with a Rabbit phone. Not encouraging for a network intending to be a cheaper alternative to a mobile phone.

Perhaps if the handsets had been much cheaper the system would have brought in more customers, and the base station network would have expanded to the point at which it became a more attractive proposition. As it was the arrival of GSM mobile phones brought in a similarly-priced but just better digital system which offered universal coverage and incoming calls, and by the end of 1993 the network was dead. The Rabbit base stations and handsets could be found from surplus suppliers for the rest of the ’90s as slightly unusual cordless home phones, but otherwise it survives only in a handful of decaying pieces of signage that can still be seen from time to time as you travel round the UK. [Ringway Manchester] features some of them in the video below the break.

There’s a footnote to the CT2 story in the European DECT digital telephone system. This was intended to be the replacement for CT2 and has the specification of a fully-functional 3G cellular phone system including a data layer as well as its common use as a domestic cordless phone, but never achieved that potential. The networks and manufacturers had had their fingers truly burned by cordless handsets, and wouldn’t be looking anywhere but GSM for the rest of the decade. Today one of the very few places you’ll find a functioning public DECT mobile network is in our community, in the form of the networks at European hacker camps provided by Eventphone.

Did any of you have a CT2 phone? Was it better or worse than our assessment? Tell us in the comments.

Header image: Jmb, CC BY 2.5.

Post a Comment