Design Solutions For The Heat Crisis In Cities Around The World

It was 1999 when Smash Mouth dropped the smash hit All Star, stating “The ice we skate is getting pretty thin, the water’s getting warm so you might as well swim.” Since then, global temperatures have continued to rise, with no end in sight. Political will has been unable to make any grand changes, and the world remains on track to blow through the suggested hard limits set by scientists.

As a result, heatwaves have become more frequent, and of greater intensity, putting many vulnerable people at risk and causing thousands of deaths each year. This problem is worse in cities, where buildings and roads absorb more heat from the sun than natural landscapes do. This is referred to as the heat island effect, with cities often being several degrees warmer than surrounding natural areas. It’s significant enough that experts are worried some cities could become uninhabitable within decades. Obviously, that’s highly inconvenient for those currently living in said cities. How bad is the problem, and what can be done?

The Heat Has To Go Somewhere

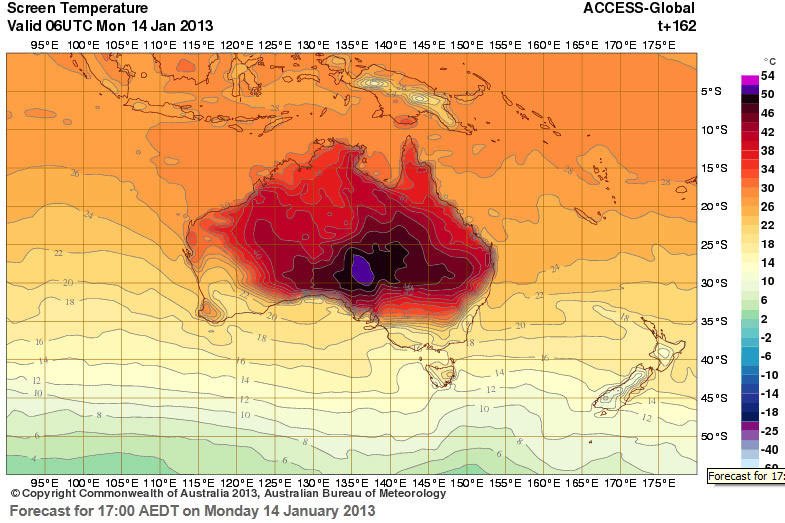

Cities like Sydney, Australia are starting to face ambient summer temperatures of up to 50°C, which can be unbearable to exist outside in for more than a few minutes. Worse, surface temperatures can far exceed this level.

Bitumen roads and carparks can hit 80°C, which among other things, makes it very hard to walk back to your car at the beach. Playgrounds have seen even higher surface temperatures, potentially causing burns to unsuspecting children out on a hot day. With temperatures this high, simple solutions like fans fail to make much difference; powerful air conditioning is the key to surviving summer. Many elect to visit shopping centres for extended periods if their homes aren’t suitably equipped.

However, it’s not a problem that can simply be air-conditioned away. The power grid isn’t always up to the strain, particularly in developing countries, and the increased energy use only further drives carbon emissions into the atmosphere, potentially exacerbating the problem. Instead, cities must look to deal with the excess heat in other ways. There are two main ways to attack the problem — reducing the temperature level, and adapting the city to better deal with excessive heat.

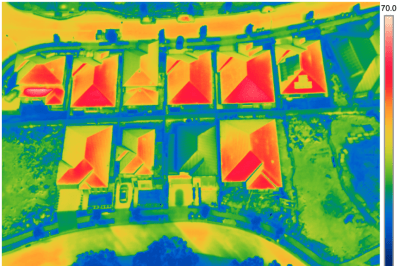

Reducing Heat Through Building Materials and Green Spaces

Reducing the temperature level can be done with simple techniques, but achieving a large effect is difficult. Covering roofs with lighter colored or more heat-reflective materials can make a difference, by reducing the amount of heat absorbed by a building and thus re-radiated into the surrounding environment. California has already taken steps in this area, through its Title 24 code that mandates minimum requirements for new roofs and renovations. This has the added benefit of keeping the individual building itself cooler, reducing the load on air conditioning, too. Research is ongoing to develop coatings to reduce the heat absorbed by roads, too. Other mitigating measures involve increasing green space in cities. Trees and grasses can have a cooling effect on their surroundings, however, they must be properly irrigated to do so. With space at a premium in many modern cities, architects are experimenting with ‘green’ buildings covered in plants. Maintenance can be difficult, though, and the plant life can come with a risk of pests. These measures are all useful, but modelling suggests the gains are modest — only bringing down ambient temperatures by a couple of degrees. Surface treatments and greenery could be enough to stop you burning your feet when you run outside to get the mail, but it won’t solve the broader issue.

Designing for Hotter Conditions

Bringing out the bigger guns involves adapting cities to be more livable at higher temperatures. This can involve a broad spectrum of measures. It could be something as small as building shaded shelters at train stations to keep passengers out of the sun, or as extreme as building housing and commercial buildings underground to keep them cooler.

There’s precedent for this, in the Australian town of Coober Pedy. Founded as an opal mining town in 1916, it regularly faces temperatures over 45 °C (113 °F). As the opal boom subsided, many former underground mines were turned into homes, hotels and shops. Buildings underground can be 10-20 degrees cooler than the outside ambient temperature, a major gain with the tradeoff of little to no natural light and more complex construction. It’s unrealistic to expect to sink entire existing cities beneath the Earth, but there are simpler measures available too. Installing efficient air conditioning and good insulation can go some way to making existing buildings more livable, albeit at the expense of higher energy costs.

Regardless of the measures taken, none are cheap or a silver bullet. Some cities will rise to the challenge, while others will see population outflows as residents seek comfort in more liveable spaces. Humanity has abandoned cities to ruin before, and it will likely happen again — but for an altogether new reason this time.

Post a Comment