Bare-Metal STM32: Please Mind The Interrupt Event

Interruptions aren’t just a staple of our daily lives. They’re also crucial for making computer systems work as well as they do, as they allow for a system to immediately respond to an event. While on desktop computers these interrupts are less prominent than back when we still had to manually set the IRQ for a new piece of hardware using toggle switches on an ISA card, IRQs along with DMA (direct memory access) transfers are still what makes a system appear zippy to a user if used properly.

On microcontroller systems like the STM32, interrupts are even more important, as this is what allows an MCU to respond in hard real-time to an (external) event. Especially in something like an industrial process or in a modern car, there are many events that simply cannot be processed whenever the processor gets around to polling a register. Beyond this, interrupts along with interrupt handlers provide for a convenient way to respond to both external and internal events.

In this article we will take a look at what it takes to set up interrupt handlers on GPIO inputs, using a practical example involving a rotary incremental encoder.

Some Assembly Required

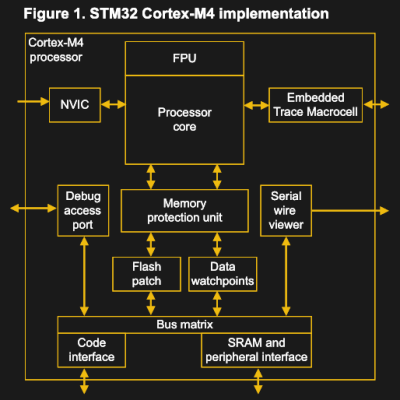

Interrupts on STM32 MCUs come in two flavors: internal and external. Both types of interrupts use the same core peripheral in the Cortex-M core: the Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller, or NVIC. Depending on the exact Cortex-M core, this peripheral can support hundreds of interrupts, with multiple priority levels.

These interrupts are not all freely assignable, however. If we look at the reference manual for the STM32F4xx MCUs (specifically RM0090, section 12), we can see that for the NVIC interrupt lines, we get whittled down to 82 to 91 maskable interrupt channels from the up to 250 total for the NVIC core peripheral in the Cortex-M4.

These interrupt channels all have a specific purpose, as defined in the vector table (e.g. RM0090, Table 62), which has over 90 entries. Some of these interrupts are reserved for processor, memory or data bus events (e.g. faults), while the ones which are usually most interesting to a developer are those related to non-core peripherals. Just about any peripheral — whether it’s a timer, USART, DMA channel, SPI, or I2C bus — has at least one interrupt related to them.

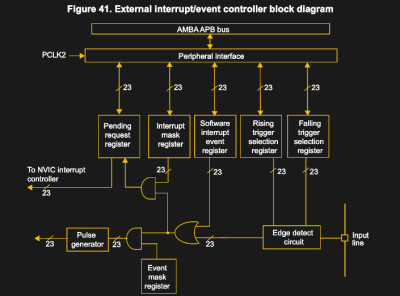

The same is true for the EXTI (EXTernal Interrupt/event controller) peripheral. On the STM32F1, F4, and F7 STM32 families, the EXTI peripheral has 7 interrupts associated with it, and 3 on the F0 (STM32F04x and others). For the first group, these are described as:

- EXTI line 0

- EXTI line 1

- EXTI line 2

- EXTI line 3

- EXTI line 4

- EXTI line 5 through 9

- EXTI line 10 through 15

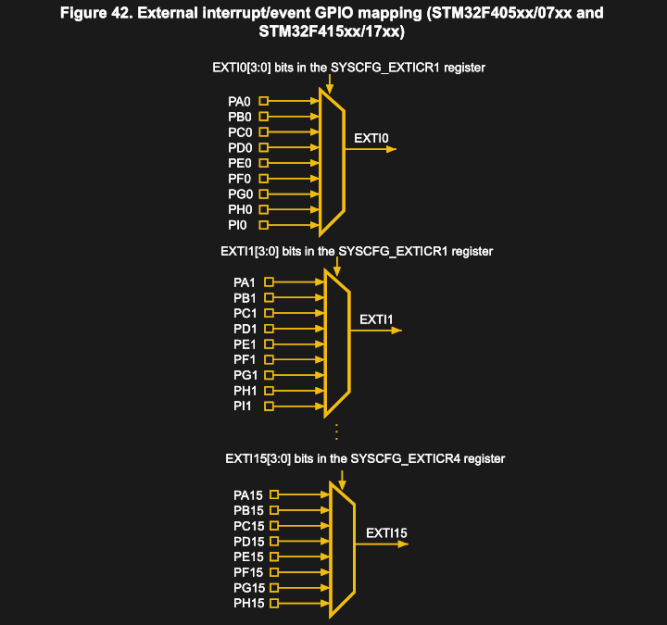

As one can see, we get 16 lines on the EXTI peripheral which can be used with GPIO pins, but some of those lines are grouped together, requiring a bit more work in the interrupt handler to determine which line got triggered if desirable. The lines themselves are connected using muxes to GPIO pins as in the following diagram:

What this means is that on the F1 through F7 families, GPIO pins 0 through 4 get a dedicated interrupt which they share with other GPIO peripherals. The remaining 11 pins on each GPIO peripheral get grouped into the remaining two interrupts. On the STMF0xx family, lines 0 & 1, as well as 2 & 3 and 4 through 15 are grouped into a total of three interrupts.

The remaining EXTI lines are connected to peripherals like RTC, Ethernet, and USB for features like Wakeup and Alarm events.

Demo Time: Incremental Encoders and Interrupts

The way that mechanical rotary incremental encoders work is that they alternately create a contact between the single input pin and the A & B output pins. The result is a pulsing output from which one can deduce the rotation direction and speed. They are commonly used in control panels, where an additional two pins provide a push button functionality.

In order to properly sense these pulses, however, our code that runs in the MCU has to be aware of every pulse. Missed pulses will result in visible effects to the user such as a sluggish response in the system, or even a direction change that doesn’t get picked up immediately.

For this example, we’ll use a standard rotary encoder, connecting its input pin to ground, and connecting the A & B pins to GPIO inputs. This can be any combination of GPIO pins on any port, as long as we keep in mind that we do not overlap with pin numbers: if we use, say, PB0 for signal A, we can not use PA0 or PC0 for signal B. We can however use PB1, PB2, etc.

Setting Up External Interrupts

The steps involved in setting up an external interrupt on a GPIO pin can be summarized as follows:

- Enable

SYSCFG(except on F1). - Enable

EXTIinRCC(except on F1). - Set

EXTI_IMRregister for the pin to enable the line as an interrupt. - Set

EXTI_FTSR&EXTI_RTSRregisters for the pin for trigger on falling and/or rising edge. - Set

NVICpriority on interrupt. - Enable interrupt in the

NVICregister.

For example an STM32F4 family MCU, we would enable the SYSCFG (System Configuration controller) peripheral first.

RCC->APB2ENR |= (1 << RCC_APB2ENR_SYSCFGCOMPEN_Pos);

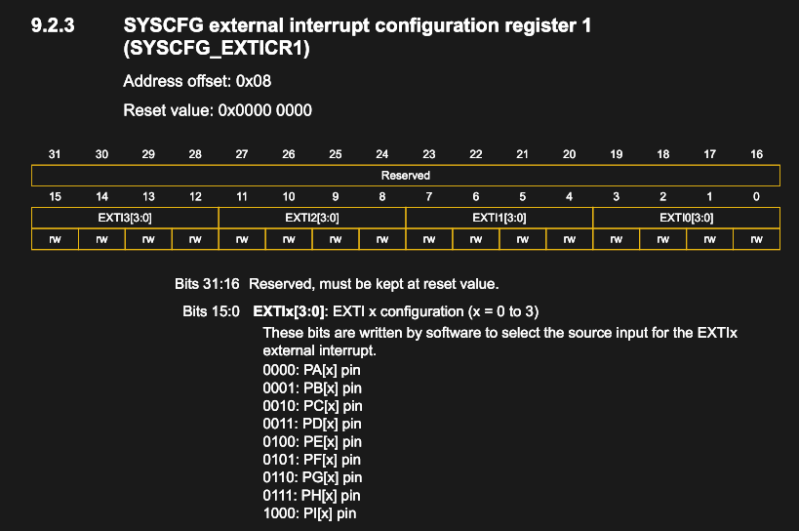

The SYSCFG peripheral manages the external interrupt lines to the GPIO peripherals, i.e. the mapping between a GPIO peripheral and the EXTI line. Say if we want to use PB0 and PB4 as the input pins for our encoder’s A & B signals, we would have to set the lines in question to the appropriate GPIO peripheral. For port B, this would be done in SYSCFG_EXTICR1 and SYSCFG_EXTICR2, as each 32-bit register covers a total of four EXTI lines:

While somewhat confusing at first glance, setting these registers is relatively straightforward. E.g. for PB0:

SYSCFG->EXTICR[0] |= (((uint32_t) 1) << 4);

As each line’s section in the register is four bits, we left-shift the appropriate port value to reach the required position. For PB4 we do the same thing, but in the second register, and without left shift, as that register starts with line 4.

At this point we’re almost ready to configure the EXTI & NVIC registers. First, we need to enable the GPIO peripheral we intend to use, and set the pins to input mode in pull-up configuration, as here for PB0:

RCC->AHB1ENR |= (1 << RCC_AHBENR_GPIOBEN_Pos); GPIOB->MODER &= ~(0x3); GPIOB->PUPDR &= ~(0x3); GPIOB-&>PUPDR |= (0x1);

Say we want to set PB0 to trigger on a falling edge, we have to first enable Line 0, then configure the trigger registers:

pin = 0; EXTI->IMR |= (1 << pin); EXTI->RTSR &= ~(1 << pin); EXTI->FTSR |= (1 << pin);

All of these registers are quite straight-forward, with each line having its own bit.

With that complete, we merely have to enable the interrupts now, and ensure our interrupt handlers are in place. First the NVIC, which is done most easily via the standard CMSIS functions, as here for PB0, with interrupt priority level 0 (the highest):

NVIC_SetPriority(EXTI0_IRQn, 0); NVIC_EnableIRQ(EXTI0_IRQn);

The interrupt handlers (ISRs) have to match the function signature as defined in the vector table that is loaded into RAM on start-up. When using the standard ST device headers, these have the following signature:

void EXTI0_IRQHandler(void) {

// ...

}

When using C++, be advised that ISRs absolutely need to have a C-style function symbol (i.e. no name-mangling). Either wrap the entire ISR in an extern "C" {} block, or forward declarations of the ISRs to get around this.

Wrapping Up

With all of this implemented and the encoder wired up to the correct pins, we should see that the two interrupt handlers which we implemented get triggered whenever we rotate the encoder. Much of the code in this article was based on the ‘Eventful’ example from the Nodate project. That example uses the APIs implemented in the Interrupts class from that framework.

While at face-value somewhat daunting, using interrupts and even setting them up manually as described in this article should not feel too intimidating once one has a basic overview of the components, their function and what to set the individual registers to.

Using the NVIC and EXTI peripherals for detecting external inputs is of course just one example of interrupts on the STM32 platform. As alluded to earlier, they serve a myriad more purposes even outside the Cortex-M core. They can be used to wake the MCU up from a sleep condition, or to have a timer peripheral periodically trigger an interrupt so that a specific function can be performed with high determinism rather than by checking a variable in a loop or similar.

It’s my hope that this article provided an overview and solid basis for further adventures with STM32 interrupts.

Post a Comment