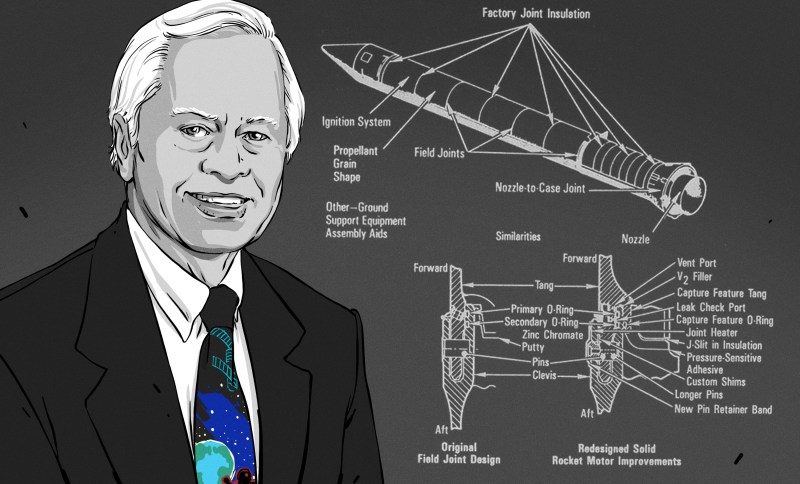

Allan McDonald’s Legacy And The Ethics Of Decision-Making

The Space Shuttle Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986 was a life-altering event for many, ranging from people who had tuned in to watch the launch of a Space Shuttle with America’s first teacher onboard, to the countless people involved in the manufacturing, maintenance and launching of these complex spacecraft. Yet as traumatizing as this experience was, there was one group of people for whom their dire predictions and warnings to NASA became suddenly reality in the worst way possible.

This group consisted of engineers at Morton-Thiokol, responsible for components in the Shuttle’s solid rocket boosters (SRBs). They had warned against launching the Shuttle due to the very cold weather, fearing that the O-ring seals in the SRBs at these low temperatures would not be able to keep the SRB’s hot gases from destroying the SRB and the Shuttle along with it.

Allan McDonald was one of these engineers who did everything they could to stop the launch. Until his death on March 6th of 2021, the experiences surrounding the Challenger disaster led him to become an outspoken voice on the topic of ethical decision-making, as well as a famous example of making the right decision, no matter how difficult the circumstances.

What Should Never Have Been

Allan J. McDonald was born on July 9, 1937, and grew up in Billings, Montana. He grew up the son of a grocer but did not follow in his father’s footsteps. After graduating from Montana State University with a degree in chemical engineering, he began to work for Morton-Thiokol in 1959. This company had made a name for itself in the production of solid rocket boosters (SRBs) and was contracted in the late 1950s for the Minuteman ICBM program.

As the Shuttle program got under way, Morton-Thiokol was contracted to produce the SRBs for the Space Shuttle in August of 1972, which saw McDonald among the engineers in charge of the Shuttle SRB program. By that time SRBs were familiar technology, and had its share of opponents and proponents. Boeing was among those who argued for liquid-fueled boosters, while even SRB proponent McDonnell Douglas stated in a 1971 report that they saw case burn-through, where hot gases escape along the side of the SRB, as a fatal scenario without recovery possible.

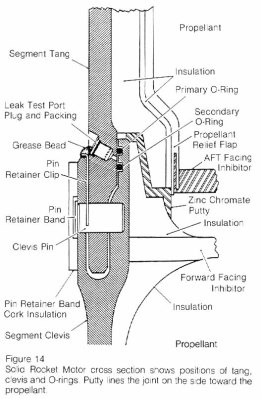

When comparing liquid-fueled and solid rockets at the time, it was found that SRBs overall were more reliable, which was a major concern with the manned Space Shuttle program. The issue of burn-through was thought to be sufficiently solved by using two O-ring seals at each joint between SRB segments. Unfortunately it was later found that flexing of the segment casing could occur during ignition, where the pressure inside the SRB would cause a gap to form between a seal and the segment.

This ‘joint rotation’ problem was seen as an issue by NASA engineers, who would write to the manager of the SRB program, George Hardy, to note their concerns. Despite this, the first Space Shuttle missions used this joint design, even after STS-2’s SRBs showed clear signs of the O-rings being eroded from hot gases passing by them. Since these SRBs were reusable, they were inspected after each recovery, with the SRBs used with the 1984 STS-41-D mission showing both the primary and secondary O-ring being degraded. With 1985’s STS-51-B mission (also flown by Challenger), it was found that hot gases had escaped past both O-rings, much like they would a year later.

Despite these joint issues and hot gas blow-by during launches being a well-known issue at NASA and Thiokol, no measures were taken to improve the design, leading to the fateful Challenger launch on that cold January 28 in 1986.

Guilt

The Space Shuttle’s SRBs were rated to launch in temperatures down to 4 °C (40 °F), yet temperatures on the targeted launch day were considerably below that, at a predicted −1 °C (30 °F), with overnight temperatures down to 18 °F (−8 °C) . On January 27, during the launch preparations of Challenger‘s tenth mission (STS-51-L), Thiokol engineers — including Allan McDonald — and managers discussed the weather conditions with NASA and Marshall Space Flight Center.

At this point Thiokol engineers were well-aware that the O-ring joint solution was far from ideal, and they pointed out that they could not guarantee the joints would even seal properly at temperatures below 54 °F (12 °C) as the rubber became less flexible and thus less able to seal the segment joints at those low temperatures. They argued for the launch to be postponed until temperatures increased.

What happened next is unfortunately all too well-known. NASA managers continued the launch after Thiokol management relented and overrode the guidance from their engineers. These engineers, including lead engineer Allan McDonald, Bob Ebeling, and Roger Boisjoly thus found themselves watching the Challenger launch the next day, praying that nothing would happen, while dreading the worst.

During the Shuttle’s ascent, everything appeared nominal, with the Shuttle performing its normal maneuvers. It almost seemed like nothing would go wrong. Then within seconds Challenger disintegrated, with the two SRBs spiraling away from the remnants of the Space Shuttle and the main tank. For those watching on from the ground, there was nothing that could be done to save any of the seven souls onboard.

For the Thiokol engineers who had tried to warn NASA, this was devastating. For Ebeling, who had written a desperate memo about this issue in 1985, the grief and feelings of guilt never went away.

Not a Unique Case

During the subsequent investigation it was found that much like with previous launches, one of the seals had failed, and hot gases made their way outside of the SRB, near the struts holding it to the main tank. Initially a seal made of aluminium oxides from the SRB’s burned propellant sealed the gap, but after a sudden wind shear rattled the SRB, this temporary seal failed and the escaping hot gases were free to finish their destructive work. This is just what Thiokol’s engineers had feared, and something for which they had seen strong warnings on previously recovered SRBs.

President Reagan formed the Rogers Commission in June of 1986 to investigate the incident. The commission’s findings were that the O-ring design flaw lay at the root of the accident, while strongly criticizing the decision to launch. Their report concluded that:

… failures in communication … resulted in a decision to launch 51-L based on incomplete and sometimes misleading information, a conflict between engineering data and management judgments, and a NASA management structure that permitted internal flight safety problems to bypass key Shuttle managers

McDonald and Boisjoly were two of the Thiokol engineers who testified as witnesses for the commission. Their truthfulness led to McDonald being demoted at Thiokol, while Boisjoly resigned from his position at Thiokol. However, members of Congress learned of McDonald being sidelined and threatened Thiokol with exclusion from future NASA contracts. Thiokol management relented, resulting in McDonald being promoted to vice president, and put in charge of the redesign and re-qualification of the SRBs for future Shuttle missions.

None of this explains exactly why NASA was so adamant to launch, even if communication between engineers and upper management was poor, as found by the Rogers Commission. Especially after decades of clear concerns about the joint seals and clear evidence of pending disaster. For a situation where the safety of those involved should be paramount, one could call this decision to launch a callous disregard for human life.

The Price of a Life

Sometimes the price of progress comes at a cost, as with Apollo 1, which saw unfortunate design decisions lead to the death of three people. Such accidents stand in stark contrast with accidents like the Challenger disaster, however. In hindsight, the Apollo 1 design was flawed, but mostly as a result of the rushed development during those days of the Space Race against the Soviet Union, unfortunate shortcuts were taken and painful lessons learned.

In the case of Challenger, there was no rushed development, but a supposedly finished orbiter with active sister spacecraft and many years of mission data that would — and did — reveal the weaknesses in the design. As the Rogers Commission concluded, the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster was ‘rooted in history’, with NASA subsequently trying to cover up having ignored the objections from engineers.

None of this is exclusive to the space industry either. As we have seen recently with the Boeing 737 MAX, and in the past with cases like the Ford Pinto and Therac-25 radiation therapy machine, wilful and unethical decisions. By rushing a product to market, cutting corners to save costs, or by omitting certain testing or design elements, a situation is created in which people are likely to get injured, or even killed.

The Way Forward

Both Allan McDonald and Roger Boisjoly would spend a lot their time after the Challenger disaster telling people about what happened, and especially the circumstances that led up to the disaster. McDonald’s book on the disaster titled ‘Truth, Lies, and O-rings’ from 2009 goes into depth on what happened.

Both of them would speak at seminars and other events, to impress on people the need to do the right thing and make the right decisions, or as McDonald put it: ‘do the right thing for the right reason at the right time with the right people’. Regret for the things which one did are tempered by time, whereas the regret for things we did not do will always remain.

During the decades after the Challenger disaster, McDonald had to deal with the feelings of guilt over those lives that were lost, but came to realize that he had no reason to feel guilty. He, along with his fellow engineers had after all done the right thing, at the right time, with the right people.

Even though their pleas and objections fell on deaf ears, the guilt and responsibility was not theirs to bear. He, along with those who went ahead, now have left the responsibility to do the right thing with the next generations. All so that in the future there shall be no more engineers watching on as the disaster they feared unfolds in front of their very eyes.

Post a Comment