Fixing nRF24L01+ Modules Without Going (Too) Insane

Good old nRF24L01+ wireless modules are inexpensive and effective. Well, they are as long as they work correctly, anyway. The devices themselves are mature and well-understood, but that doesn’t mean bad batches from suppliers can’t cause hair-pulling problems straight from the factory.

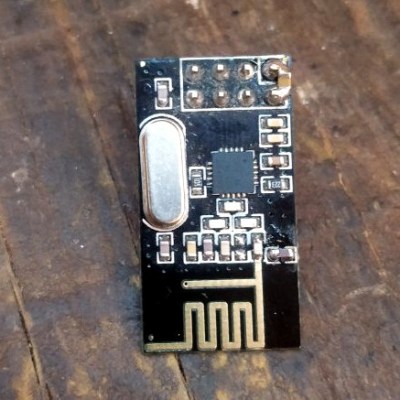

[nekromant] recently got a whole batch of units that simply refused to perform as they should, but not because they were counterfeits. The problem was that the antenna and PCB design had been “optimized” by the supplier to the point where the devices simply couldn’t work properly. Fortunately, [nekromant] leveraged an understanding of the problem into a way to fix them without going insane in the process. The test setup is shown in the image above, and the process is explained below.

This issue wasn’t new to [nekromant], as previous batches had suffered from a “magic finger problem”, where bad performance is magically solved by placing one’s finger on the antenna. This had been fixed in the past by soldering in a missing 1.0 pF capacitor, but the newest batch of nRF24L01+ units was so bad that something more needed to be done. Simply adding a 1.0 pF capacitor was no longer enough, and it’s unclear exactly why.

For reasons likely related to the PCB antenna, each radio required adding a capacitor in a value usually somewhere between 1.0 pF and 2.2 pF. But there was no way to tell which value any particular board would need. To solve this, [nekromant] made a small test rig to profile each device in turn by sending packets and measuring how many failures were recorded. After profiling each device, fixing them was a matter of informed trial-and-error. Once putting a finger on the PCB antenna begins to worsen a device’s performance rather than improve it, that module (along with whatever value of capacitor was last soldered onto it) could be dropped into the “OK” bin, and the process repeats until the pile is gone.

[nekromant] points out that the obvious lesson here is to be careful about picking suppliers, but that’s increasingly difficult to do with modules like these. An annoying manual board rework process is one thing for a small hobby project, but would be quite another issue entirely if several hundred or thousand units were involved.

Counterfeit silicon wasn’t the issue this time, but maybe brush up a little on spotting counterfeits all the same.

Post a Comment